The Mormon Church renounced poly-gamy more than I00 years ago, but in Northern Arizona, a fundamentalist sect of “believers” is still playing by the old rules – men are taking two or three “wives,” fathering dozens of children and collecting millions in welfare. It’s been going on for decades, without much uproar, but now, the kids are running away and the attorney general has vowed to protect them.

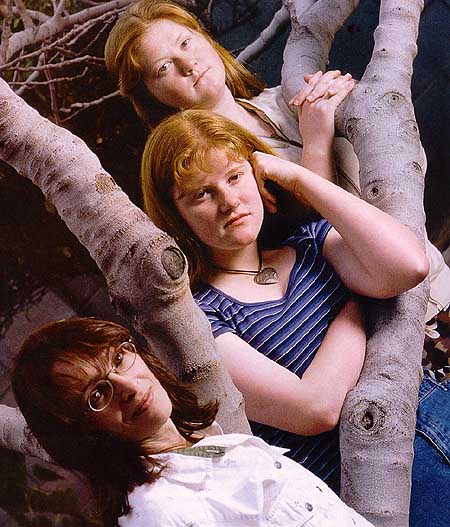

They could be sisters, or certainly cousins, these two pretty redheads curled up on a sectional sofa in a North Phoenix “safe house.” Both of their names are Fawn, and together, they’re known as “the two Fawns” – as though they’re lost baby deer. And in a sense, they are, these two runaways from the polygamist community of Colorado City, which straddles the Arizona-Utah border.

They say they ran and sought safety with strangers because they feared that their families would marry them off to old men against their will; that they’d be wife No. 3 or No. 5, and would spend the rest of their lives with the “sister wives” who take turns being bedded by the man of the house. They feared that they’d be reduced to nothing but “breeding machines” – all in the name of a cult disguised as a religion.

These young girls say they know there must be more on the outside – that girls out here can get an education, can have a say in their own lives, can be spared from a culture where sex with a child is not only condoned, but encouraged. They say they had to flee to survive.

They come from a very strange, closed community of fundamentalists who have been excommunicated from the Mormon Church. People there believe a man can’t enter heaven without having had at least three wives, and a woman can’t get there at all without having been married to a polygamist man.

Polygamy is the heart and soul of Colorado City, which was called Short Creek back in the 1950s, when Arizona last tried to do something about the city’s unlawful multiple marriages. Today, Colorado City has the largest concentration of polygamists in North America.

This is a strict society in a remote corner of Mohave County, where men rule with an iron hand in the name of God – men who father hundreds of children and then are supported by millions of dollars of welfare.

This is a demanding society that forbids radio and television, limits education for its children, and demands total obedience to a man who calls himself a “living prophet.”

This is an insulated society where inter-marriage is so prevalent that most of the young girls resemble the two Fawns. It’s a society where young men aren’t seen as the future of the community, but as competition for the old men interested in the young girls – the young men are often forced out of town.

This is a settlement and a way of life that is very hard for outsiders to understand. And the two Fawns are the latest evidence that many insiders don’t want to live this way, either.

So, these 16-year-olds ran. Friends of friends found them a safe house in Utah. Then, a Valley activist swooped in with TV crews in tow to take them to Phoenix, where a friendly woman gave them shelter.

And it was on the heads of these two little girls that the state of Arizona had finally staked its claim to end decades of negligence or indifference to what happens every day inside the cult on the Arizona Strip – child abuse, rape, bigamy, slavery.

But once again, Arizona failed miserably. And the girls ran from the state with the same fear they felt when they ran from their parents.

One lawmaker who has fought for years to draw attention to Colorado City and the plight of girls like the two Fawns says it amounts to “the Taliban in our own back yard.”

The first few days after they ran, the two Fawns had no idea they’d be-come the rallying cry for a new resolve to save the children of Colorado City.

They had more immediate needs. They’d left with only the shirts on their backs, and if one of their boyfriends hadn’t given them some money, they’d have been penniless. They had no toothpaste or deodorant. They didn’t even have a comb for their long red hair.

The night they ran in mid-January was the first night they’d ever slept outside their parents’ homes. They arrived in Phoenix in the middle of the night – a city with more lights than either girl had ever seen in her lifetime. They were left with a woman they’d never met, and all the while they were sure the mighty power of Colorado City would appear and take them back. And, of course, they knew very well that the state of Arizona had a lousy record of dealing with runaways from their town – normally turning the girls back to their parents under the theory that “family reunification” was the primary goal of Child Protective Services (CPS).

The girls were so needy and scared that they bonded almost instantly with the stranger who offered them protection – within 24 hours, they were calling this woman “mom.”

Meeting with state officials, however, was different. Their first meeting went very badly – although the attorney general’s office had promised that the girls could stay in the safe house, the CPS worker hadn’t gotten the message and told them they’d have to go to a group home. So, they fled again, running from that meeting while the adults trying to help them placed frantic phone calls to clear things up.

The day after that encounter, the girls were told the CPS worker had simply been mistaken, and they could stay with “mom.” But they were still skittish and nervous.

They were lounging at either end of the sectional in the safe house. The television was on, and they were watching it curiously. Slowly, haltingly, with fragmented sentences, they started talking about how lousy their lives had been.

Then the phone rang and the safe house “mother” took the call. “We have to go,” she announced with some urgency. “Your parents are meeting with CPS, and we don’t trust them to not tell where you are.”

The girls gave each other frightened looks, and needed no prodding to jump up. They stuck their stockinged feet into shoes and the safe house mother grabbed her purse. Everyone ended up on the patio of a Sonic restaurant – “What’s a Sonic?” the girls asked.

They each ordered large peanut-butter fudge shakes and shared mozzarella sticks. And then they told stories that make you want to cry.

Penny Peterson knows everything the two Fawns have to say, because she experienced it all 20 years ago when she, herself, was a runaway.

Today, she’s a Phoenix mother of five, with a loving husband and a new home and a life that has brought back the infectious laugh that had been beaten out of her in Colorado City.

And she’s become Arizona’s most effective tool in fighting polygamy.

“I have 39 brothers and sisters, three mothers, one dad,” she says. “My mother was wife No. 1, and she has 18 children. I was the wild child – always hyper, a tomboy, my dad’s favorite. He always said, ‘I’ll never be broke because I’ll always have a Penny left.’ He was everything to me; he was like my God; I worshiped him. My mom would beat the shit out of me, I think because she was jealous. Then I was 12 or 13 when he molested me.”

She went to her mother, Rose Stubbs, with the devastating news about her father, David. “She let him beat me with bailing wire,” Penny remembers, and she winces as she utters the words.

She knew then, she says, that she was on her own.

She already had a good look at what life in this community was like. “It might look like Mayberry on the outside – everyone happy and smiling – but that’s not what it’s like inside those homes,” she says. “The stress level is so high. The wives are bitterly jealous of each other – vicious to one another. You’ve got moms beating on the other mother’s kids. And the work is darn hard. When I was 9 years old I was taking care of 22 kids for weeks at a time. For those inside, this is all they know. The world out here is like a twilight zone.”

Her one release “from all the crap” was the horse she’d wildly ride through the hills around Colorado City – an ugly, unkempt town set in a breathtaking stand of mountains. And she started running away – one time, she even got as far as Flagstaff. But she was always found and taken home.

She says she does have one happy memory about growing up there. That is, until she starts to think about it.

“The greatest day for a girl in Colorado City is when you have your eighth-grade graduation,” she says. “You get to wear a fancy dress like a prom dress. Your hair is all fixed up. That is your day. I had a hot-pink taffeta dress, a little Cinderella dress – it almost got me kicked out of graduation, but my mom did stand up for me, and I got to go. Here were all these girls as pretty as they could be, and we were so proud of ourselves. And only later did I realize all those old men were sitting there checking out the fresh meat.”

She knew what was planned next. “After eighth-grade graduation, we know that we’ll be married off, and we just cross our fingers and pray he is not old, wrinkly, mean and ugly.”

Penny saw her worst fears coming true when her 15-year-old best friend was married off to a 48-year-old man who she calls “a jerk.”

“He raped her on their wedding night, and every night after. He said he wanted me to be his bride, too. I decided, no way – I’d die or get out of here before he touches me.”

She called friends she’d made in Las Vegas, where her dad often took his kids to sell wood and hay at swap meets. Penny’s friends drove out, bringing guns just in case, and then took Penny home with them. For the next couple of years, she earned her way doing odd jobs, always fearing someone would come along and drag her back to Colorado City.

She finally made a deal with her dad – she sent him half her paycheck, and he promised to let her stay out.

And then eight years ago, her father came asking for Penny’s help. “Two of my little sisters, just 12 and 14 years old, were being courted by Orson William Black,” she says. “He was 43, and already had four wives, including my older sister, Rosie.”

“Black believes he’s his own prophet and my mother is one of his followers. She is trying to get all her daughters married to him. Dad opposed the marriages because he thought Roberta and Beth were too young.” But her dad was helpless to stop the marriages because her mother had gotten a restraining order against him to keep him away from the girls.

So Penny got on the phone and called anyone she thought might help: CPS, the FBI, the IRS. “I was giving information and telling them anything they wanted to know,” she remembers. “The FBI and IRS came and interviewed me, but they didn’t help. CPS stopped taking my calls.”

Roberta was 12 when Black married her and “hid her away”; she had a 3-year-old son before any of her family saw her again, and when they did, they couldn’t believe it was the same girl. “Roberta was always a beautiful tomboy, but he messed her up,” Penny says. “She can’t even create a sentence, her mind is gone.”

Black married Beth when she was 14. “My mom wanted it and pushed it. This whole time, I’m screaming to anybody who’d listen,” Penny says. Nobody was listening.

So Penny decided to build the case against Black the only way she knew how: She went “undercover,” befriending her mother and sister, Rosie, pretending she didn’t oppose Black; milking the women for information. She discovered even more devastating news: Rosie had previously been married and had I0 children before marrying Black. She now offered him her own 13-year-old daughter, Sally Beth, Penny’s niece. Penny alerted CPS, “but they screwed up again,” and the next day, Black fled to Mexico with his ever-growing family. Since then, Penny has learned Rosie has offered yet another daughter to her husband, a girl named Vashti, who’s just turned 13.

Last year, the state of Arizona indicted Black on five felony counts of child abuse and bigamy. The charges are pending because Black is now a fugitive, living somewhere in Mexico.

It might not sound like much, Penny admits, but you have to put it in perspective: “These were the first charges in Arizona in 50 years!” Behind her eyes, it’s obvious that she’s mentally calculating how many Beths and Robertas were lost in all those decades.

“I wanted justice for my sisters.”

And then her sister Ruth showed up at the door of her Phoenix home.

“Ruth was a beautiful girl – healthy, vivacious, full of piss and vinegar. But she shows up here devastated, rundown, dark-eyed. The first couple months she slept, and I took care of her and her two kids.”

Ruth had been married off at 16 as the third “spiritual wife” of Rodney Holm, a police officer in Colorado City who lived on the Utah side of town. By now, Penny had a whole rolodex of numbers for Arizona officials. She called them, and they called Utah, which prosecuted Holm for bigamy and unlawful sex with a minor.

He was convicted. “He got a year’s jail time, and they let him out on work release,” Penny says with disgust. “Big whoopty-do. Talk about a slap in the face.”

“These men hide behind the skirts of polygamy – they call it their religion,” Penny notes. “In their minds, it’s normal to check out 13-year-old girls. That’s what they’re taught. But to me, it’s not far to go from there to messing around with 12- or 11- or 10-year-olds, or messing around with your own young daughter. It’s just more and more perverse.”

The longer she talks about the culture of polygamy, the angrier she gets: “Women are worth nothing – they’re basically cattle. A man owns five or six and has as many calves as he can – the more you have the bigger stud you are. It gives them braggin’ rights. And somewhere in their twisted minds, they think this means they’ll get into celestial heaven.”

If she could save them all – all those girls who are taught they have only one option in life and have no say over their futures – she’d do this: “I’d educate all the kids in public schools; no one would be allowed to marry under the age of 18, and I’d give the girls a choice – if you did that, you’d abolish polygamy right there. An educated 18-year-old who has a choice isn’t going to want to be somebody’s third or fifth wife.”

And she’s not giving up on nabbing William Black. “The most important thing to me is I need to get him brought to justice. Pretty soon, he’ll run out of my nieces, but he’s not going to stop. He’s sick.”

For as long as she can remember, 16-year-old Fawn Holm has been taught that if she didn’t obey the prophet, she’d burn in hell. “Fawn, you’re sick in the brain, and you’re going to hell,” she remembers her father, Carl, snarling at her.

Her immediate family includes her mother, Esther, who had 19 children – Fawn being the youngest – and a second mother named Venita, who is her mother’s niece and is the mother of 15 children.

She has nothing nice to say about her father. “I don’t know him,” she says. “I never loved him, so I tried to stay away. Every morning at six he makes all the kids get up for song and prayer and reading. One day I wouldn’t get out of bed, and he was shaking my butt and pulled me out, and I hurt my back. But father said he had an inspiration that I shouldn’t go to the doctor. I’m still in a lot of pain.”

And then she makes a declaration that shows she knows exactly why she ran: “I’m not his property – he told me he could do whatever he wants because I’m his property.”

She complains that her father never showed her love, was always “trying to make my life miserable,” and took her out of school because “he told me that girls didn’t need to go to school.” And he was very clear in his message about her worth: “My dad would always be telling us girls to prepare ourselves to be married.”

She remembers she never fit in and was often in trouble. “I’d let my hair hang [girls are supposed to wear braids], and I wore pants once and really got in trouble [girls are supposed to wear clothes that cover them from neck to ankle]. People said we were the whores of the town. They don’t even know what the word means. We just yelled back, ‘Yeah man.'”

Part of her contrary behavior was a survival technique. From watching the community, teenagers know this: Very bad kids are married off early so they can’t leave the community; good kids are willingly married off at 14, but “kind of bad” kids are made to wait until at least 16 for marriage so they can be trained to be good kids.

From where she sat, Fawn Holm saw being “kind of bad” as a good thing.

But the other embedded lesson she learned was that the prophet was godly. Fawn remembers that when her father read the Bible, he would substitute Prophet Warren Jeffs’ name for the Biblical characters, including Jesus. She does know about the “heavenly father,” Mary, Jesus, heaven and hell, but has never heard of purgatory, or mortal and venial sins.

Some of the prophet’s notions have left her with a distorted look at love and marriage: “You’re not supposed to love for love, you’re supposed to love for the priesthood the men hold,” she says. And at first, you think she knows that it’s misguided. But then she adds this: “The heavenly father gave sex to us to have children. I believe sex isn’t a fun thing to do – it’s something you do to have children.”

But she is clear – incredibly clear – that she has no interest in going back to Colorado City.

“I’m scared of what they’ll do to me if I have to go back,” she says. “They’ll keep us locked up until we decide to get married. I’m sick of being scared. I’m sick of them telling me I’m going to hell. They’re not even my family anymore. I don’t even miss them. It’s sad to say, but I don’t.”

She’s asked what she’d do if her parents showed up right now, and she throws a frightened look at the street running in front of the Sonic. “I would run,” she says with anger in her eyes. She’s asked what she’d like to say to her family if she could safely address them, and she flashes her two middle fingers in a crude gesture of defiance.

After she calms down, she says she’d like to tell them: “I proved you wrong. You always told me if I tried to leave it wouldn’t work. But I’m going to make it work.”

She wants to get a job so she can support herself until she gets married and has a family and raises them “like I never was raised.”

She never wants a polygamist family, but doesn’t condemn those for whom it works. “If they want to do it – if they’re happy that way and the man loves them both, then they should do whatever makes them happy.”

She says she just wants a chance for happiness herself.

Later, a call to her family home in Colorado City is answered by a woman. A baby is crying in the background. Upon hearing that a reporter is on the other end, doing a story about Fawn, the woman hangs up.

But the mother of the second Fawn – Fawn Broadbent – doesn’t hang up. She wants to talk about a daughter she doesn’t expect to see much anymore.

“I‘ve known she didn’t want to be part of our community, and that was fine – they have a choice,” Catherine Broad-bent says over the phone. “I just asked her to wait until she was 18 so she’d be old enough to support herself.” But her daughter was too impatient to wait, she adds.

“She doesn’t want to come back, and she’s not going to be forced to,” says the mother of 14, who is the only wife of Matthew Broadbent.

She approves of her daughter being adopted by the other Fawn’s brother, who now lives in Salt Lake City after having left Colorado City years ago. Although she doesn’t know him, she has talked with his wife and feels comfortable they’d be good to her daughter. “It’s way better than just [being] on the street,” she says.

What does she want people to know about her daughter? “She really is a sweetheart. Anybody who gets to know her knows she’s just sweet. We’ll miss her.”

But even though the family will know where Fawn will be living, Mrs. Broadbent doesn’t expect much contact. “Salt Lake is quite far, we have limited income, and I don’t foresee us doing much together,” she says. “I hope she calls me and lets me know she’s OK.” She says her daughter has promised to phone regularly.

“I love her, and I want her to be happy and safe – and I’m not saying it’s not safe here because it is; but that’s a personal, religious choice and every person has the right to choose. That’s what America’s about. I am strong in my belief, and I think if everyone did understand, then they’d feel the same way. But they don’t understand, and they don’t want to, and I’m not here to convince them.”

Her daughter, Fawn Louise, says she wishes her parents had been more open to her choices before she was forced to run. “I tried going through The Front Door, and I bet you don’t even know what that means,” she says. “I went to the prophet and told him I wanted to leave. That’s The Front Door. I was told to stay with my father and do what he wants. He told my dad in two years I would be turned around. My mom says, ‘The prophet says you’re going to make it,’ and she meant I’d marry somebody and have a billion kids. So I had to go out The Back Door.”

She dreams of being a fashion designer, and says she wants something very simple: “I want to be able to make choices in my life, not be forced.”

Flora Jessop has been working to get girls like the two Fawns that simple freedom for over a decade. She’s the one who drove up to Utah that night in mid-January to bring the girls back to Phoenix. She bought them a week’s worth of clothes when they got to town, arranged for their safe house, and has been their protector and ally ever since.

Jessop, herself, is a runaway from Colorado City, and she’s founded a group called “Help the Child Brides.” She’s a skinny little thing with a tenacity that doesn’t stop. And she’s inspired more than one official to take all of this seriously.

But she hasn’t been able to save the one child who made her an activist: her little sister, Ruby. Flora ran from Colorado City the day Ruby was born – May 3, 1986. Fourteen years later, Flora was devastated to learn that Ruby had been married off to an older man. Ruby eventually fled, but was found by members of the church and taken back. Flora tried to alert officials that her sister had been kidnapped, but they did little to help.

Because of Flora’s constant agitating, members of the polygamist community – officially known as the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints – were forced to take Ruby to Utah officials, where the frightened girl said everything was fine and was sent back. Flora says she knows that Ruby has had at least one child, but she hasn’t had any news of her little sister in a couple of years.

And so she tries to save other girls – tries to alert others in power that something must be done.

One person she’s convinced is state Senator Linda Bender of Lake Havasu City, whose blood pressure visibly rises when she talks about the goings-on in the polygamist community of her district. “It’s so disgusting, you can’t believe this is happening,” she says. “It’s total bondage and slavery. We yell at other countries about their treatment of women and children, but we have the equivalent of the Taliban in our own back yard.”

She’s been trying to amend Arizona’s criminal code to make polygamy a crime – it’s forbidden by the constitution, but there’s no correlating criminal penalty. So far, she’s been rebuffed by a Legislature where several leaders can trace their own family histories of polygamy.

Flora has also influenced Valley author Betty Webb, whose 2002 novel, Desert Wives: Polygamy Can Be Murder, got incredible national reviews, but was totally ignored by the local press.

Publishers Weekly said, “This book could do for polygamy what Uncle Tom’s Cabin did for slavery.” The New York Times said, “If Betty Webb had gone undercover and written Desert Wives as a piece of investigative journalism, she’d probably be up for the Pulitzer.”

Yet, she says she got zero coverage in Arizona, where the book is set, and where its fictional location is really Colorado City.

Webb says she’s still mystified why Arizona has been so complacent for so long, especially since the welfare fraud is costing state taxpayers millions of dollars.

“The prophets are no better than pimps because polygamy is all about money – it’s about old men making money off these girls,” she says. Because polygamy is illegal, the men legally marry only one woman, taking the rest as “spiritual wives,” who are considered single in the eyes of the state, so their offspring are eligible for welfare payments, Webb explains. “The longer the breeding life, the more money there is – if you don’t breed until the girl is 20, you missed out on having seven kids that can collect welfare.”

Webb says she’s encouraged the media is now focused on this issue, but worries that it won’t last. “I think as soon as the din dies down, everybody will go back to their own lives and forget about it.”

But two local reporters are trying to assure that doesn’t happen: Mike Watkiss of Channel 3 and John Dougherty of Phoenix New Times.

Watkiss, who has been covering this story almost from the day he began his journalism career 25 years ago in Utah, was born a mainstream Mormon – a religion that once practiced polygamy but renounced it so Utah could be admitted to the Union in 1896. He can look back at great-grandfathers who were polygamists, but that’s not what sparked his interest in investigating polygamy.

“I was furious at how this story was covered by the national media,” he says. “They treated it like a giggle, ‘Oh, here’s a guy with six wives, how does he do it?’ I knew it wasn’t funny. This is child abuse, this is sex exploitation, this is no different than the Taliban – they just don’t take them into the public square and behead them.”

Dougherty has been on the story, too. For the last year, he’s been producing one probing story after another, unmasking the sins of Colorado City. In fact, he actually moved to that area to devote himself to the story. “I’d spend the day going through public records and the nights trying to meet with families in their homes,” he says.

Dougherty has filed more than 70 public-record requests, documenting the millions of tax dollars spent each year to support the “pligs” (short for “polygamist pigs,” an offensive slang word that’s used both inside and outside the community). “Arizona is spending over $10 million [in welfare, food stamps, and health and education benefits] in Colorado City alone,” he says. Utah is spending about the same amount in the companion city of Hildale.

He also discovered that polygamists had removed all their children from the public school system, but still controlled the school, and are “looting it blind.” The district is about to go under from the squandering of taxpayer money, including the purchase of a $220,000 Cessna 210 airplane.

He found that 33 percent of the town’s residents receive food stamps, compared to the state average of 4.7 percent. All in all, the people in Colorado City receive $8 in government services for every dollar they pay in taxes. (Elsewhere in Mohave County, folks receive about a dollar of services for every dollar in taxes they pay.)

“All America should be concerned about what happens when religion runs rough-shod over civic authority; that’s what’s happening in Colorado City,” Dougherty says.

It didn’t take him long to understand why this community gets away with it. “Colorado City votes in a bloc,” he says. “You have 1,000 to 1,500 votes – that’s pretty powerful in a small county.”

But you don’t have to resort to political conspiracy theories to understand why these men and their taste for little girls have gone unpunished. All you have to do is remember the name Short Creek.

Arizona and Utah officials – including the Quorum of Twelve Apostles of the mainstream Mormon Church – have repeatedly tried to stamp out the polygamist colony known as Colorado City, a place formerly known as Short Creek.

On July 26, 1953, Arizona Governor Howard Pyle ordered a pre-dawn raid on Short Creek by the Arizona National Guard, police and county officers. They rounded up 122 polygamous men and women, whose 260-some children were bused to foster homes in Kingman, some 400 miles away.

Pyle explained the unprecedented raid in a public statement: “Here is a community – many of the women, sadly, right along with the men – unalterably dedicated to the wicked theory that every maturing girl child should be forced into the bondage of multiple wifehood with men of all ages for the sole purpose of producing more children to be reared to become more chattels of this totally lawless enterprise.”

As righteous as that sounded – as much as Mormon officials had helped plan the raid, as much as the Deseret News lauded Pyle for helping clean up Short Creek “once and for all” – most of the country saw the raid as religious persecution.

Papers around the country ran photographs of crying children being wrenched from their parents, and the men and women of the community gave interviews complaining they were law-abiding citizens just trying to practice their religion in a nation where freedom of religion is sacrosanct.

Arizona’s largest and most influential paper of the day, The Arizona Republic, criticized the raid as “a misuse of public funds.”

Short Creek destroyed Pyle’s political career. The next year he was voted out of office. Within three years, all those arrested had been released from jail, were reunited with their families, and resumed their polygamous lives.

And adding salt to the wound, the little 400-resident town of Short Creek soon attracted new converts to the fundamentalist cult that knew further government interference was unlikely. Today, Colorado City and Hildale have some 9,000 residents combined.

For the past 50 years, it’s basically been hands-off, as every government official feared “the ghost of Short Creek.”

But now things have started to change, thanks in part to the tenacity of a few journalists, the courage of a few girls, the strength of a handful of activists, the attorney general of Utah and the newest player in the battle, Arizona Attorney General Terry Goddard.

In early February, the first Arizona official to publicly address a news conference about Colorado City in five decades stood behind the microphone and told the crowd, “I will not tolerate child abuse.”

Attorney General Terry Goddard also made it very clear where he wasn’t going to go: “This is not an issue of religion, it’s not an issue of culture, it’s not an issue of lifestyle. First and foremost, this is an issue of child safety.”

Goddard has taken a bill to the Legislature that will make “child bigamy” a felony – if passed, it would punish both parents and men who marry or cohabitate with a minor.

He’s also asking lawmakers for more money to hire attorneys who can specialize in rural law enforcement. And he’s pushing for a “public safety facility” in Colorado City where teens who want to escape can go. As it is, the remoteness of Colorado City makes running away or seeking help very difficult.

Goddard notes that since last fall’s special legislative session, CPS has a new focus: No longer is “family reunification” the first priority, but instead, it’s “child safety.” He said he hopes that message reaches Col-orado City to help overcome “50 years of distrust.”

But what eventually happens to the “two Fawns” will say more than any pronouncement or good intention.

On Valentine’s Day, the two Fawns each penned letters to their safe-house “mother” and to Flora Jess-op, who’d rescued them.

They left the letters behind as they fled once again, and their words clearly explain why: “I was hoping that Arizona would help me,” Fawn Holm wrote, “but I thought wrong…. I left because all they seem to want to do is send us back to… like prison. Well, I won’t go back, so I guess I’m going to be running until I’m 18. I can’t thank you guys enough, but thanks for trying.”

Fawn Louise Broadbent wrote this: “I am afraid I will be sent back to Colorado City, and I do not want to go back because I will be locked up and even married. I am not happy with CPS because they are not doing their job and are lying… I need some help so I can have a life.”

Their safe-house mother reports that officials from CPS and the attorney general’s office both frightened the girls into believing they would be sent back or sent to a lockdown group home in Mohave County. CPS officials have said they had no intention of sending the girls back.

But the safe-house mother says she’d like to confront officials with this question: “All we ever asked for was a guarantee that you wouldn’t send them back, and you never gave it – how can you now tell the media that, when you wouldn’t tell it to the girls?”

Waiting in the wings is a gentle, patient man from Salt Lake City who hopes he’ll be al-lowed to adopt both of the Fawns – one is his blood sister, the other is her friend.

Carl Holm and his wife, Joni, rushed to Arizona when Flora Jessop called to say his baby sister had run from Colorado City. “What can I do to help?” he remembers asking her. “She asked if I’d take them, and I said, ‘Yes, of course.'”

Carl Holm fled Colorado City himself some 20 years ago.

“I know what goes on down there, and I don’t want Fawn to have to go through that,” he says. ‘ He was about 8 years old when he realized his “normal” family wasn’t nor- mal anymore. “I woke up one morning, and a lady’s purse was on the kitchen table, and my mother was sleeping on the sofa, and someone was with my dad.” He was told, “This is your second mother – call her Aunt Venita,” and he remembers his bafflement.

But for the past 20 years, he’s been estranged from a family that includes 39 children. “Even though I have this huge family, I don’t have a family,” he says sadly. “My wife and I have four daughters – they’re my only family:”

Carl Holm says he rejected all religion for a while, unable to get rid of the “sour, bitter taste,” but three years ago converted to mainstream Mormonism. And last November, his daughter was married in the Temple in Salt Lake City: “That was a really big and proud moment for us,” he says, as his wife nods her head in agreement. “My parents wouldn’t come. They wouldn’t even come to the reception. That really hurt.

“What I want to give to Fawn [is the understanding that] at least she has a brother. I’ll help both girls get an education, will give them a place to live, will feed them and will be a family to them.”

Carl Holm is a maintenance mechanic with one daughter still at home. He acknowledges that taking on two more teenagers will be a financial hardship. “I have the support of my church,” he notes. “Our Ward has given us beds, and will help with whatever is needed.”

He knows it will be a significant job to take in these two girls and bring them into adulthood. “My sister is five years socially behind her age,” he says. “And she hates her family: I know the feeling. There was a time I hated them so bad I wanted to kill. But she has to get over the hatred, or it will just eat her up.”

He promises to be there to help.

But he knows – as more and more people are beginning to understand – that there’s a whole community on the Arizona Strip where thousands of other girls like the two Fawns are still in real danger.