For a reporter covering the news in the ’70s, the landscape was a little different, especially Downtown, where officials tried to put a freeway over Central Avenue.

Oh my God! Arizona owns the purple mountains majesty,” I yelled into the tape I was recording for a friend as I drove into my new home state. That was back in March of 1972.

As a child of the Midwest – of tabletop-flat eastern North Dakota, to be precise – even simple hills impress me, so you can imagine my excitement when I saw the beautiful mountains that greeted me as I left Texas and drove into Arizona. I was taking the “southern route” because I was pulling a U-Haul filled with antiques I’d stored while a graduate student at the University of Michigan.

So, there I was, me, all of my possessions, and my vinyl-topped Buick LeSabre cruising on I-10 toward Phoenix to start a new life in a state whose politics and terrain were strange and seemingly hostile. “There’s a cactus,” I squealed into the tape. That was soon followed by: “That’s all there is – cactus everywhere. And everything is brown.”

The first real sign of life was Tucson, but that was quickly followed by mile after mile of tedious desert – to this day, that drive is still one of the most boring in the nation.

Tempe, however, looked like a real oasis. “They’ve got these giant “pineapple” things – palm trees, I suppose,” I said to my tape recorder. “At least there’s some grass here,” I added with hope.

The next day, some new friends at The Arizona Republic, where I was hired as a reporter, took me into Phoenix to look for an apartment. “I’d like to live in a brownstone,” I told them as they laughed. “Or Downtown,” which brought tremendous giggles and looks of “you poor child.” I soon learned that Phoenix had never had brownstones, and I’d arrived as the Downtown it once had was being abandoned as folks fled to the suburbs.

I arrived in Arizona knowing little about the state, other than the fact that Barry Goldwater, “Mr. Conservative,” was the big kahuna, and the AAA map showed a coiled rattler as the state’s symbol. For a liberal terrified of snakes, it wasn’t a happy moment.

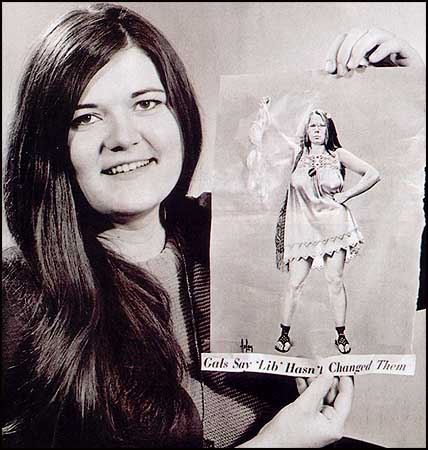

What’s more, I knew absolutely nothing about the desert environment, I’d never met a Mexican-American, I had no clue that there was a difference between Navajos and Hopis, and I thought we’d already settled the debate that women and men were equal. Boy, I had a lot to learn.

One thing I did know, though, was the words to By the Time I Get to Phoenix – I’d rewritten them to announce to my relieved friends that I’d finally found a job: “By the time I get to Phoenix, I’ll be working!!!”

As it were, I came to Phoenix because of the incredible insight and intelligence of Bob Early – then the Republic’s city editor – and his assistant, Connie Koennen. I had a master’s degree in journalism and urban affairs from one of the nation’s best schools; I had previous newspaper experience on The Flint Journal (Michigan); I already had a national award in my back pocket; and I possessed all the enthusiasm of a 26-year-old who expected Phoenix to be little more than a stopover.

Instead, the Phoenix I discovered – the Phoenix that would keep me here all these years – continues to take my breath away, and not always in a good way!

When I came to Phoenix, there was no convention center and no Symphony Hall. The state’s tallest building – the bank at Van Buren and Central – was under construction, and in those days, it was known as Valley Bank (now it’s Bank One, and it’s still the tallest building in the Valley).

Phoenix had just celebrated its 100th birthday, with a reception at The Adams Hotel, which is not there anymore – I watched it “imploded” to make way for the Sheraton that now sits at the corner of Adams and Central. The Centennial Ball was held at the Hotel Westward Ho, which, back then, was a grand spot, but now is used for HUD housing. There were a couple of decrepit Victorian mansions near Central Avenue and Encanto Boulevard, which were torn down or moved away to make room for the high-rises that currently sit next to the new Victorian “urban mansions” under construction. Talk about a circle of life.

When I rolled in, there was a movie house at Central and Palm – it had the best popcorn in the city – and a Bob’s Big Boy at Central and Thomas. (I’m still trying to find Bob’s “secret sauce” somewhere.) High-rises now occupy both of those spaces. I also remember that Downtown was without any movie house for decades.

Farther north, in those days, Bell Road was a two-lane road (and not always paved) that formed Phoenix’s northern boundary. It now marks the “heart” of the northern expansion that’s more than doubled the size of this city since I arrived.

At the other end, South Phoenix was famous for the flower gardens that used to line Baseline Road. Today, only a couple of those gardens still exist. Their loss is one of the mortal sins of this city.

Off to the east, Scottsdale embraced its “West’s Most Western Town” slogan, and Tempe was more famous for Monti’s restaurant than its university, which reminds me of a story that’ll give some perspective.

While in graduate school, I’d worked for the News Bureau at the University of Michigan, so I was accustomed to turning to professors as experts. I’d only been at The Arizona Republic for a couple weeks when I went up to the city desk and asked to borrow their ASU directory. They didn’t have one. They suggested that I might find one in the sports department. That was the day I realized that the state’s largest newspaper thought the nearest state university was irrelevant. And it would stay that way for a long time, until the likes of Lattie Coor and Michael Crow showed us what a great university can be.

When I first got into town, I could still shop at JC Penney Downtown, and have lunch at the Woolworth’s counter. And had I known Spanish, I could have gone to the Spanish movie theater in the Orpheum, which had such promise but needed so much work to bring it back to its glory. (Thank goodness that finally happened.)

I could also go to Phoenix’s first “shopping center” – Park Central, built in 1957 – where there were three major department stores, along with restaurants, a druggist and a fine bookstore. I watched the Hyatt Regency being built, wrote about the controversy of tearing down a city block to build Patriot’s Park in the heart of Downtown, and helped make the Rosson House a reality. As it turns out, that’s one of my favorite memories.

I remember being saddened when I saw the only standing Victorian home in Phoenix being reduced to a flophouse. But that’s what had become of the Rosson House, once one of the city’s grandest homes. At the time, its lovely downstairs rooms had been partitioned off with sloppy drywall and awful paint – creating small single rooms that barely had room for a hot plate. One day, I went over and started knocking on doors, interviewing a few of the residents, and taking note of how decrepit the grand old lady had become. I wrote a story for the Republic bemoaning how this landmark had gone the way of everything else that was old in Arizona – unloved, untended, uncared for.

That’s what happens, the story noted, in a town that’s almost nobody’s “hometown”; in a state filled with transients – there’s no sense of history or tradition.

Not long after I wrote that, Phoenix Mayor John Driggs pulled my story out of his pocket after a Council meeting and told me that he, too, was saddened by the lonely fate of the Rosson House. Maybe it’s because John Driggs was a man whose family had been a part of Arizona tradition; who did respect the old. Whatever it was, he vowed right there to do something. And he did. He marshaled the Junior League of Phoenix, who lovingly restored the old place to its Grand Lady status, and today, it’s the centerpiece of Heritage Square at Monroe Street, between Fifth and Seventh streets.

By the way, there’s no better time to visit the Rosson House than December, when the house is decorated for a Victorian Christmas and is open for tours. Talk about taking your breath away!

I have to be honest and report that one of my first substantial memories of Phoenix was laughing at how silly she could be. Shortly after arriving, I was sitting in a Park’s Board meeting when the lights were lowered for a slide show on the long-awaited Papago Freeway.

By then, I already knew the mantra: Phoenix had fewer freeway miles than any city in the country, and because of that, its growth was stymied. The Republic had championed the cause of building freeways for nearly two decades, and an entire network was on the books. But most of the roads were little more than pipe dreams, because there wasn’t any money to build them.

Not so for what locals called the Papago Freeway, but was officially the last urban stretch of I-10. There was federal money for that, and Arizona was anxious to spend it. The state had been buying up the right-of-way for years, and had already torn out thousands of homes and businesses just south of McDowell. (Anyone who wants to track the demise of Downtown needs to look no further than that massacre of the Downtown neighborhoods.)

The moment those lights at the board meeting were dimmed, you felt certain that the Papago Freeway was on the verge of being built. Right or wrong.

I remember seeing the slides of the freeway design and laughing out loud. I thought it was a joke, and I was amazed that nobody else was laughing. The freeway they intended to build soared 100 feet above Central Avenue, and cars got up to that point on giant “helicoids” – much like the circular parking garage at Sky Harbor’s Terminal 4. The only difference was that these things were enormous – just how big had never been discussed publicly, I soon discovered.

Nobody at the Republic much cared that I found this design ridiculous – or that the shadowed “alley” below it would become a kind of Berlin Wall between Downtown and everything north. I remember getting brushed off, but I didn’t let go. I started asking a lot of questions about the design, and how the plan came together, and why Phoenix thought it was such a great idea to tear apart its central city for ribbons of concrete.

That’s when I wrote what might have been the first critical story ever printed in The Arizona Republic about the sacrosanct Papago Freeway. It was a front-page story that detailed the enormity of those helicoids and how they’d destroy even more neighborhoods as they were built. If I remember correctly, each one was the equivalent of several football fields in size; each one would have eaten up more of the city’s historic neighborhoods and would have dumped intolerable amounts of traffic into the few streets that remained.

The story sent shock waves throughout the city. The pro-freeway folks couldn’t believe their staunch ally would expose such information, while the anti-freeway folks started a noisy campaign to spotlight all of the problems the freeway would create.

I was shocked that in all the years of loyal support for that freeway, that nobody at the state’s largest and most influential daily newspaper had ever bothered to ask such a simple question: Just how big are those helicoids?

As it turned out, there were lots of questions nobody had ever bothered to ask. But things turned around quickly.

The Republic started printing all kinds of anti-freeway stories, sometimes giving voice for the very first time to folks with extremely good data to show that the freeway would be a disaster. It’s also true that pro-freeway viewpoints were relegated to minor roles in those stories, many of which I wrote. I remember some of my friends arguing that it was as much an abuse of power to be one-sided against something as it was to be one-sided for it. Obviously, they had a valid point.

Eventually, a citizen’s group, fueled by the Republic, demanded a public vote on the building of the Papago, and in 1973, the voters said NO. There’d be two more votes in the coming years, and in the end it was passed by voters, but only after massive design changes that put the central city section of the freeway underground, rather than overhead. That is how we ended up with Margaret T. Hance Park, which sits above the Papago Freeway. And that is how we saved the historic neighborhoods of Phoenix, one of which I call home. Frankly, that’s not a legacy I regret.

Looking back, so much has changed over the years. The Arizona sun destroyed the vinyl top on my LeSabre. I came to love and admire the Barry Goldwater I was fortunate enough to know. And I ended up Downtown after all – an area that’s coming back with a vengeance, thanks in part to ASU’s new Downtown campus.

It took me a long time to see the purple and magenta of the desert’s pallet, but it didn’t take long for me to realize that this is where I belong. This is home.