Seven of 16 leadership positions in the Arizona Legislature are held by Mormons, including the top spots in each chamber. That’s anything but insignificant, but how significant is it?

There’s a 10,000-pound elephant sitting in the middle of Arizona, and nobody wants to mention it. It’s whispered about in public, and gossiped about behind closed doors. But you won’t find it dissected in the newspapers of Arizona; you certainly won’t find it mentioned on Valley TV stations; and even talk radio stays away.

In fact, I’m warned that I can’t even bring it up without sounding like a bigot.

But the question needs to be asked in the open: Is it significant that both chambers of the Arizona Legislature are led by Mormons? Is the political landscape of this state being strongly influenced by this politically active and conservative minority group?

I’ve been asking that question, and have heard a resounding “yes.” I’ve also heard things that are disturbing and amazing.

Of course, Independent gubernatorial candidate Dick Mahoney didn’t help the issue last fall when he ran a frankly racist advertisement during his unsuccessful gubernatorial campaign.

His ad basically warned that Republican gubernatorial candidate Matt Salmon wouldn’t do anything to help the women and children trapped in a polygamist community on the Arizona-Utah border, because Salmon is a Mormon.

I remember cringing when I first saw the ad, and then getting progressively angrier every time it ran. Of course, nowhere in the ad did Mahoney bother to mention that the Mormon Church outlawed polygamy a hundred years ago. Nor that the small group of renegades that persist in plural marriages have been excommunicated from the Mormon Church.

You’d think a Roman Catholic like Mahoney would be sensitive to this kind of bashing, considering how his own religion has been badly misrepresented over the years, but I guess not. And, of course, the ad begged the question: If the polygamists were safe only because a Mormon might be governor, why have they thrived while Catholics and Protestants have occupied the governor’s office over the decades?

The criticism of Mahoney’s ad was warranted. However, I do think the wholesale condemnation – from religious leaders, politicians, editorial boards and ultimately, the voters – made everyone gun shy about any mention of religion influencing public policy. Unfortunately, Dick Mahoney set back honest discussion of this issue by his racist ad.

I went to the Capitol to ask my questions because Mormons – a minority of lawmakers – hold these positions in the Legislative leadership: Senate president and House speaker (the two highest ranking offices), Senate majority whip, Senate minority leader, House majority leader, House appropriations chairman, and House rules chairman (who has the power to kill any legislation).

When The Arizona Republic recently ran a story on the five “most influential lawmakers,” four were Mormons.

So I asked the Capitol press corps what this all meant, and I was told this:

- “We’ve always had a small little Mormon caucus in the Legislature because we’re told they’re very civic-minded, but it’s more pronounced this year.”

- “Everyone is most afraid of the right-wing Mormons who not only have taken over the Legislature, but the Republican Party. If you cross them here, they’ll get you at election time – that’s their trump card.”

- “There’s a fine line between lawmakers voting their conscience and imposing their religious beliefs, and that’s where we are now.”

- “Don’t forget former lawmakers like Stan Turley. He’s a reasonable, sensible, honorable man, and a Mormon. But the militants we have in the Legislature now are nowhere near Stan Turley.”

- “I suppose there are fruitcakes in every religion – we just seem to have an inordinate number of them in the Legislature.”

I then asked the question of lobbyists, and here’s what I was told:

- “The Legislature is a public entity and it shouldn’t be about religion.”

- “To discuss it is to raise the religious persecution angle, and nobody wants to go there.”

- “People don’t want to talk about it because they’re afraid of retribution.”

- “Every one of the moderates in the House has been threatened with being opposed [in upcoming elections] by the ideological right wing – it’s raw politics.”

- “It’s not politically correct.”

Senate President Ken Bennett doesn’t see any real significance in so many leadership roles coming from his religious group. “If you look at the top 16 leadership roles in the Legislature, and Mormons hold seven, that’s not even half,” he notes.

Nor does he think the East Valley is as dominated by Mormons as many perceive (although the term “East Valley” has become the code phrase for Mormons in state politics). “There’s five districts in the East Valley, and in only one are all three lawmakers Mormon,” Bennett notes (that’s District 22, the power base for powerful House Majority Leader Eddie Farnsworth). But two East Valley districts have no Mormon lawmakers, and two others have two Mormons each.

“That’s seven out of 15 lawmakers in five districts who are Mormons,” Bennett notes. “I don’t perceive them as a bloc – that doesn’t translate into an East Valley Bloc. In fact, it doesn’t cross my mind.”

He also maintains there is “no Mormon agenda.”

“Our faith teaches family values and hard work and the golden rule,” he notes. “If our role in the Legislature means anything, it means people with these values are in key positions. But I don’t think our faith has a corner on these values.”

“There is no Mormon agenda,” agrees Senate Minority Leader Jack Brown, who is the most unusual Mormon in the Legislature, being the only member who’s a Democrat.

“The only things are abortion and gambling,” he adds. “We’re strongly pro-life and we’re anti-casinos and lotteries.”

“There’s always been a pretty good little group of Mormons in the Legislature,” he says. “We take a pretty active part in things. Yes, Mormons take a greater role in voting; we believe it’s our obligation to take on civic responsibilities.”

But he rejects the idea that being Mormon means you speak with one voice. “In East Mesa we have a group of ultra-ultra-conservatives, and then there’s me – I’m not liberal, but I’m not that conservative, and in the Mormon Church, we have room for all kinds.”

Others, however, don’t see it that way.

House Minority Leader John Loredo, a Democrat and a Roman Catholic, says he definitely sees a Mormon agenda, and he suggests anyone who wants to know what it is just needs to examine the original budget that came out of the Arizona House.

That budget has been widely criticized as “draconian” because it cut to shreds such important things as education, child welfare programs, healthcare for the working poor, and even money to shelter domestic violence victims.

Loredo says he’s watched major policy shifts directed by Mormon lawmakers. Among them is the charter school movement, which he says was first spawned in the East Valley. Then there was the alternative fuels crisis that threatened to bankrupt Arizona, which was orchestrated by a former powerful Mormon lawmaker, Jeff Groscost, and was heavily used by Mormon families.

I asked Loredo if we’d be having the same conversation if the Legislative leadership were dominated by Catholics. “I don’t see a united Catholic agenda – remember, you saw Hispanic Catholic lawmakers calling for the resignation of the bishop [former Bishop Thomas O’Brien, who re-signed in disgrace in June].”

Other observers agree. Journalists covering the statehouse say the closest thing to a “Catholic agenda” is opposition to the death penalty, opposition to abortion rights, and then a bevy of “social justice” issues that fight for the underdog.

But they don’t see Catholic lawmakers voting as a bloc. (The Pope’s recent call for Catholic lawmakers to do everything to oppose same-sex marriages will be an interesting test – I’m betting many Catholic lawmakers will ignore such “orders from Rome” as a case of the Pope demanding more than he has the right to ask.)

“A person’s faith should have some kind of bearing,” Loredo says. “But the faith should not control the agenda, especially when it’s offensive to other faiths.” He also objects – like legions before him – to what he sees as the superior attitude of the Mormon church. “It’s disturbing to think one group of people has the arrogance to believe they know God’s truth better than anyone else,” he says.

To be fair, I must point out that Mormons have no monopoly on religious arrogance. Catholics also believe they are the “one true” church. Fundamentalist Christians are notorious for being holier-than-thou. In fact, I remember being inflamed when I read that some right-wing religions chided pastors who attended an interfaith prayer service in New York after 9-11 because Jews and Muslims were included.

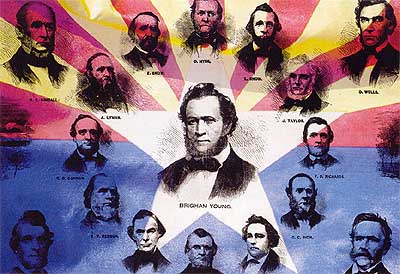

The Mormon Church has a long and terrifying history of persecution. In the early-1800s, when it was founded in Missouri by Joseph Smith, townsfolk worried that Mormons were accumulating too much political and economic power. Eventually, the “Saints” were driven out of Missouri and resettled in Illinois, where the same concerns soon cropped up. But things got worse when those fears were ignited by the “revelation” of plural marriages that would force the religion to flee west, eventually settling in Utah.

Smith claimed to have received the revelation from God, but it was kept secret during his lifetime – although he took dozens of young women as his “wives,” much to the disgust and anger of his wife, Emma. After his death, Emma worked mightily to stop the Mormons from accepting polygamy.

I must say this: If the Saints had only listened to Emma Smith, they’d have saved themselves a lot of heartache, and a lot of bloodshed and persecution. But they didn’t listen to her – in fact, women have no real voice in this faith, just as they have none in Catholicism – and the polygamy issue would mark the church for years. Considering the success of Jon Krakauer’s recent bestseller, Under the Banner of Heaven – a book the church is denouncing – polygamy is still plaguing the church to this day.

Utah wasn’t permitted into the union until it officially outlawed plural “marriages” in the late-1800s (a practice still popular with “fundamentalist Mormons”). Whether it was necessity or some core strength of the faithful, Mormon pioneers endured great hardships and struggles to help settle the West, to have an opportunity to practice their religion as they saw fit, and to control their own political destinies.

And so the most obvious thing happened: To have political power in a democracy, you need to participate in politics, and that requires you to do two things: register to vote, and then vote.

It’s no surprise that Mormons control Utah, where their religion’s headquarters dominate the landscape of Salt Lake City. And if you think about it, it should be no surprise that they’re powerful in Arizona, even though they have nowhere near the numerical strength here.

Arizona has one thing that has allowed this minority group to assume so much power: Arizona has a lazy electorate. Not only are most of our eligible voters not even registered to vote, but those who are registered don’t bother to exercise their right. It’s not uncommon in Arizona to see only one-fourth of the registered voters showing up for primary elections, and less than half showing up for general elections.

As someone who has long begged people to get involved in the political process, I’m certainly not going to criticize those who do.

If Mormons hold uncommon control over the politics of Arizona, it’s because they are uncommonly active in the political system. They are doing nothing more than we ask good citizens to do – they vote.

As one lobbyist said to me recently at the Capitol: “Instead of complaining, we should learn political activism at the feet of the Mormon Church.”