Betty Rhodes used to be a good Catholic, known as the woman with the heavenly voice. But then a priest molested her children, and suddenly, no one was listening.

Everybody told me if I took on the Catholic Church, I’d lose everything I had.” Everybody was right – Betty Rhodes did lose everything. It’s a story so sad and so infuriating, your sympathy will crowd with your anger.

You know there must be a lot of anger in Betty Rhodes. But her pretty face seldom shows it, and her soft voice seldom betrays the turmoil of her life over the past 20 years.

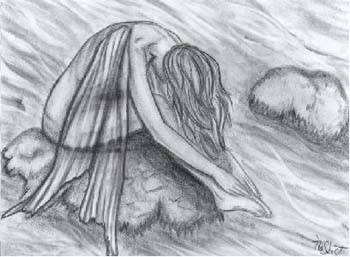

For many Catholics in Phoenix, Betty’s name will ring a bell. But it’s her beautiful singing that most will remember. The woman with the voice of an angel was the longtime music director at St. Thomas Catholic Church. She also directed a children’s choir at St. Theresa, and sang folk masses at St. Matthew. She has two tapes of religious music that were the bedrock of a very promising recording career. She was such a good Catholic woman, with such a beautiful Catholic family.

And then it all was snatched away. All because a priest molested her children.

She lost her husband, her church, her career and her faith.

We have heard often from those helpless boys and girls who were abused and molested by priests, but have seldom heard from the others who suffered: the parents and guardians and protectors who fought for their children against a church that didn’t want to hear any of it.

“They’re too busy pretending it didn’t happen to offer help,” Betty says.

Eventually, the church started to acknowledge what had happened over all those decades – awful things it tried to hide under the rug. In fact, tens of millions of dollars are being paid in penance. Sometimes, there was even an apology.

But it’s far too late for Betty Rhodes.

Betty wasn’t born a Catholic. She converted for the man she fell in love with while both were attending ASU. She married him in 1973 when she was 20, and they made a dashing pair – both attractive, both musicians, both devoted to their church. Plus, they made beautiful children. A dark-haired girl was born in 1976, followed by three blond cherubs – two girls and a boy. For nearly two decades, they could have been the poster family for family values.

“For 20 years I sang for every ordination, for Bishop [James] Rausch’s funeral, for Bishop [Thomas] O’Brien’s installation,” she recalls. (Bishop Rausch was her personal friend and had enjoyed her Chevas just three days before he died.) She earned a small stipend as music director and a tidy sum singing for some 200 weddings a year and scores of funerals.

“We always packed the mass at St. Thomas,” she explains. “In 19 and a half years, I missed six Sundays, two for having children. I was one of the primary people in the diocese [who was] into contemporary music.” Some churches wouldn’t allow music that was not traditional or not written by Catholics, so she and her husband started writing their own.

“I’ve eaten in the dining rooms of most parish houses in the Valley,” she says. Her son was named for a friend who became the bishop of Indianapolis – she sang at his ordination, too, and had his bishop’s cross specially made. “I wore it under my shirt on the plane to deliver it to him,” she says.

Her oldest daughter was 11 when it all fell apart.

She remembers her little girl coming home and telling her about the priest the kids nicknamed “Chester Molester.” To the adults, he was known as Father Mark Lehman.

He earned his nickname by coming up behind the girls and holding them up while touching their tiny breasts. It happened to Betty’s daughter at a children’s party at a water park in Mesa. He put his hands under her suit and fondled her breasts as he held her up for all to see. He pretended it was a game. The little girl knew better and told her mother.

The next day, Betty told the head priest at St. Thomas, who said he would take care of the situation.

But the following day, as she dropped her kids off at school, Mark Lehman was still on the playground, and with her own eyes, she saw him perform a “Chester Molester” move on another girl. She was stunned at how brazen he was about it. “I went to the office and pitched a fit. Again, the priest told me they’d take care of it. I said, ‘Aren’t you going to call the police?’ and he said, ‘We don’t do that.’”

“My husband said, ‘Don’t tell anyone, the church will ban you,’ but I could not believe that would happen,” she recalls. She called the police from her home.

Later, Betty discovered that her daughter wasn’t the only one of her children to be molested by Mark Lehman. She learned that her son had been sodomized by the priest, and that her other two daughters also had been molested, one as a toddler.

She reported all of it to the police. Meanwhile, her husband grew even more furious that she would challenge a “holy man,” and he soon left her.

In all, six families filed charges against Lehman. “And from that point on, nobody in church would speak to me,” Betty says. These were people she knew so well – she could tell you which pew they’d sit in each Sunday. She blames former Bishop Thomas O’Brien for blacklisting her from funeral homes, and individual priests denied her the right to sing at weddings. When one of her best friends lost her father, the family requested that Betty sing at the service. “But I was asked to leave when I showed up at the church, and that wasn’t the first or last time,” she says.

She doesn’t know who it was, but somebody threw bricks through her window, left phone threats and slashed all four tires on her car. She hardly thinks any of that was a coincidence.

“What did I do?” she asks. “I turned someone in who was hurting children. I went from earning $48,000 a year to the point [where] I couldn’t beg for a job. People said, ‘We were told you’re too much trouble.’”

She worked for temp agencies and raised her children on a stretched dime with this mantra: “faith, hope, honesty, courage, trust and love.”

The priests she had known so well, including the bishop who was the namesake for her son, “all but told me to take a flying leap,” she says. “My ex-husband told me he was offered an annulment if he could get me to stop the proceedings, and then he could marry his new wife in the church.”

She says the only call she got from Bishop O’Brien was when he called to say the church couldn’t afford any more counseling sessions for her children. “They were going to a community center where they didn’t even see the same counselors each time,” Betty says. “It cost $25 a session.”

She says she did confront Bishop O’Brien once, outside of St. Mary’s. “I told him, ‘You could have been a hero, but you did nothing, and allowed it to happen.’” She says he “just brushed me aside and walked into the church.”

She was in the courtroom with her four children and her sister the day Mark Lehman accepted a plea deal that sent him to Arizona State Prison in Florence for 10 years. Included in those charges was his confession to molesting two of her girls. There were other charges that were dropped in the plea, including the molestation of her other daughter and her son. “The church certainly didn’t want him charged with molesting a male child,” she remembers.

But what she remembers the most about Lehman’s sentencing was this: “The judge asked if he had anything to say to the families. He turned around, sneered, and said, ‘Absolutely nothing.’”

She sued the church on behalf of each of her four children and reached a settlement. Although she says she cannot disclose the amount, she acknowledges it wasn’t enough to send even one of her kids to ASU.

She never got an apology from Bishop O’Brien, who was forced to resign after his involvement in a fatal hit-and-run accident in 2003. But she did get one from interim Bishop Michael Sheehan.

The call came in at about 9:45 p.m. “He said, ‘This is Bishop Sheehan calling, and I want to apologize.’ ‘For what?’ I asked him. ‘For ruining my career or ruining my life or screwing up my kids’ lives or blackballing me or ostracizing me – what?’” The bishop, who was finally trying to say what should have been said a long time ago, hung up.

She has been told the new bishop of the diocese, Thomas Olmsted, has said that “when Betty forgives the diocese, she’ll be welcomed back in.”

What the diocese has done is unforgivable, Betty says, and she doesn’t want back in.

The good news is that all of the kids are fine now and are pursuing successful lives. It wasn’t always that way, though. Some had teenage traumas that demanded extra care.

Mark Lehman has served his 10 years and is now a free man. He reportedly lives in Central Phoenix.

Betty has found a new love and is now a grandmother. She attends a community church every now and then.

“I believed so devoutly,” she says. “I’m still in disbelief. In a million years I’d never have dreamed it would be like this.”

I listened to Betty Rhodes’ tapes while I wrote this column. One is called Eternal Faith: Music for the Liturgical Year. It is so easy to hear why she packed the church so many Sundays over all those years. There’s one song that will bring you to tears: My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

In her darkest days, those words had to haunt her. They had to remind her of everything she’d lost in trying to protect her children.

I wonder if the Catholic Diocese of Phoenix will ever realize what an angel it sacrificed.