Mainstream Mormons have been denouncing polygamy for more than a century, but the founder of the religion was all for it, even though it ultimately led to his death. What follows is a history of the radical belief, and as you’ll see, Smith’s death wasn’t the only legacy – for decades, polygamy’s been causing all kinds of problems.

Polygamy has a wild legacy. It led to the death of Mormon founder Joseph Smith. It inspired decades of religious persecution. It divided the Mormon Church more than once. It got Mormon women the right to vote. It destroyed political careers. And, lately, it’s been the focus of child abuse and the siphoning of millions of dollars of taxpayer money.

If the original Mrs. Joseph Smith had had her way, however, the “despised” notion of plural wives would have died with her prophet husband in 1844.

The mainstream Mormon Church officially banned polygamy in 1890 as a deal to ensure statehood for Utah. But fundamentalists – men and women who believe the practice is necessary to get into heaven – have continued the practice to this day.

For years, the largest concentration of polygamists in the United States has been situated on the border of Arizona and Utah, in the twin cities of Colorado City and Hildale. (At press time, the “prophet,” Warren Jeffs, was planning to move his polygamist clan to Texas.)

While claiming to be the “true” Mormon Church because of its devotion to polygamy, insiders say that what now exists is much closer to a “cult” than a religion. It’s a cult that rules through mind control, prospers by preying on minor women forced to become “child brides,” and terrorizes by cruelly destroying families at the whim of the “prophet,” who is viewed as the direct messenger of God.

However, because polygamy is illegal in both Utah and Arizona, none of the “celestial” wives are legally married to their “husbands.”

Therefore, their husbands are not required to support them, and most couldn’t afford to anyway. In addition, their offspring, and that usually means a child a year during their child-bearing years, are supported by public welfare, food stamps and state-supported medical care to the tune of millions of dollars a year.

Local historian and former Colorado City resident Benjamin G. Bistline explains it in his book, Colorado City Polygamists: An Inside Look for the Outsider: “Women are inferior to men and must learn to school their feelings, yielding to the desires of their husbands. The girls of the Colorado City polygamists are considered as chattel, to be used by the leaders to reward the faithful men of the Group for their support of the Priesthood Work. And if a man is deemed unworthy, his wives and children are reassigned to another ‘more worthy’ man. I think the biggest challenge to women in the polygamist society is their responsibility to have babies. Birth control was not allowed in any form. Women were taught… that a woman should have as many children as she could. Fifteen to 20 for one woman was not uncommon.”

Bistline writes those words not only as a student of the group, but as a father who has two polygamist daughters in the community.

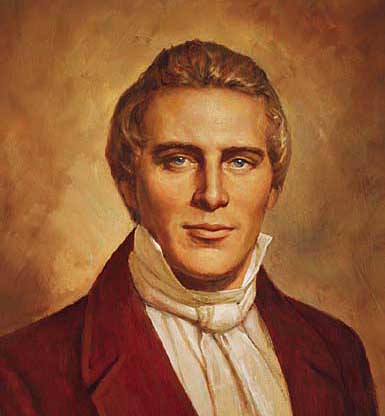

Mormon founder Joseph Smith obviously knew polygamy would be a hard sell, not only to his wife, Emma, but also to the entire flock. In a classic example of raising the flag to see which way the wind blew, he had a surrogate advance the idea of plural marriage in a pamphlet, and when it was roundly rejected by his followers, he took the political dodge of denying any knowledge of the document.

So, he kept his own polygamist activities secret – sometimes lying to both his followers and outsiders who kept hearing rumors about multiple wives – and went to his grave never having publicly acknowledged that “divine revelation” had led him to take many women as “wives.” (One historian listed 48 “wives,” but another said only 33 can be “documented.”)

Smith knew firsthand how his flock hated the idea of polygamy. In fact, he was almost castrated – but instead was tarred and feathered – for bedding a young girl in a family that had taken him and his wife into their home as boarders. As John Krakauer reports in Under the Banner of Heaven: “Despite this harrowingly close call, Joseph remained perpetually and hopelessly smitten by the comeliest female members of his flock…. He kept falling rapturously in love with women not his wife. And because that rapture was so wholly consuming and felt so good, it struck him as impossible that God might possibly frown on such a thing.”

Over time, Emma frowned enough for both of them, and she fought her husband every inch of the way. Emma had married Joseph in 1827, loved him, and expected him to honor his wedding vows of faithfulness. And she was no shrinking violet. At one point, she threatened to take a plural husband if Joseph didn’t give up his plural wives. When Joseph finally wrote down the polygamy “revelation” on July 12, 1843 – although it was still a secret within the faith – he specifically added these words, as though they came from God: “And I command mine handmaid, Emma Smith, to abide and cleave unto my servant, Joseph, and to none else….”

Krakauer goes on to write that Emma was among the first to read the document, and became apoplectic, declaring that she “did not believe a word.” And she wasn’t the only one. Smith’s second in command, William Law, didn’t believe it, either. He reportedly pleaded with the prophet to renounce the revelation, and Smith reacted by excommunicating Law. Law would then call Smith a “fallen prophet” and establish his own Reformed Mormon Church – which did not allow polygamy.

And Law did not stop there. He also bought himself a printing press, and, on June 7, 1844, printed the only edition of a newspaper he called the Nauvoo Expositor. Krakauer writes that its primary purpose was to expose Smith’s secret doctrine of polygamy, promising that future issues would “substantiate the facts.”

This not only riled the faithful, but also gave additional fuel to the outside world that already viewed the Mormons with great suspicion – the church was in Illinois at the time because it had been driven out of Ohio. Outsiders were repulsed by the constant rumors of polygamy, and also feared that the new church was growing too quickly and was becoming an economic threat. Joseph Smith himself was seen by the outside world as a charlatan and a fake. As historian Susan Myers writes in Westering Women, feelings among emigrating Eastern women were so negative toward the Mormons that they held everyone else, including minority groups, in higher esteem.

All of that heightened the reaction to William Law’s exposé newspaper. Joseph Smith demanded that the printing press be destroyed, and his followers faithfully followed suit. But the police couldn’t ignore the crime, and Smith and others were arrest-ed for destroying property and were jailed in Carthage, Illinois. The entire community immediately saw the danger of their leader being held in enemy hands, and pleaded for help.

Although the governor promised safety to Smith and his men, a mob of non-Mormons attacked the jail on the afternoon of June 27, 1844, and Joseph Smith, 38, was killed. The mob also wounded John Taylor, who was visiting Smith in jail.

Taylor would become the third president of the church. And, more importantly, he would issue a “revelation” that has been furiously debated ever since that affirmed the righteousness of plural marriage, which forms the basis for the modern fundamentalist movement that led to the founding of what is now known as Colorado City.

Upon her husband’s death, Emma Smith vowed to stop polygamy once and for all. She warned that if the next leader “is not a man she approves of, she will do the church all the injury she can,” Krakauer writes.

She joined with other anti-polygamists to install a successor. Her first choice was Joseph’s eldest son, but he was only 11 years old – obviously too young. So, the group settled on Joseph’s younger brother, Samuel, who mysteriously died soon after (some think he was poisoned by those loyal to the polygamists). After that, another anti-polygamist was named “guardian” of the church, but he couldn’t take the full mantle until there was a vote, which was scheduled for August 8.

Meanwhile, the main voice for polygamy – Brigham Young – was away, along with most of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles. Joseph Smith had not only seen himself as a direct messenger of God, but as the future president of the United States of America. In what would be the last months of his life in 1844, he announced his candidacy and dispatched hundreds of his missionaries to stump for him in all 26 states. At the time of Smith’s death, Brigham Young was in Massachusetts – he wouldn’t learn of the prophet’s death until 19 days later. He and the other apostles hurried home to Illinois as fast as they could.

If they’d have taken two days more, polygamy might have been just a footnote in Mormon history. Instead, they arrived in Nauvoo on August 6 and thwarted the anti-polygamists.

Brigham Young easily won the flock’s vote of confidence as their next leader, and that helped write history. As Krakauer notes, if Young had not been elected, “one can safely assume that Mormon culture (to say nothing of the culture of the American West) would be vastly different today. In all likelihood, the Mormons would never have settled the Great Basin [of Utah], and poly-gamy would have died in the cradle.”

Emma and her children left Brigham Young’s church – as did Joseph Smith’s mother, his only surviving brother and two sisters – and eventually ended up in the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Today, the church is called the Community of Christ and is headquartered in Independence, Missouri, claiming a quarter-million members, which makes it the largest Mormon spin-off.

As it turns out, Emma Smith wasn’t the only wife of a Mormon prophet to despise polygamy. So did Brigham Young’s “19th wife,” Ann Eliza. And in her horror, she exposed polygamy to an astonished nation, which was repulsed when it learned that in 1852, Brigham Young had declared poly-gamy a requirement for Mormons to reach the highest place in heaven.

Ann Eliza was born in Nauvoo, just after Joseph Smith’s murder, and as a baby, was part of the Mormon migration to the Utah Territory. She would later write that her life was always miserable – due to her mother’s misery under the “blight of polygamy.”

According to Krakauer: “Misery came to her as it came to all of the [Mormon] women then, under the guise of religion – something that must be endured ‘for Christ’s sake.’ And, as her religion had brought her nothing but persecution and sacrifice, she submitted to this new trial as to everything that had preceded it, and she received polygamy as a cross laid upon her.”

The beautiful 24-year-old Ann Eliza left her first husband when he flirted with polygamy, and was raising two sons on her own when she caught the eye of the 68-year-old Brigham Young. She would write that he repulsed her, but he blackmailed her into marriage – threatening to ruin her brother and have him ex-communicated if she didn’t marry him. So, she reluctantly did, but then discovered that the “Lion of the Lord” had no intention of supporting her or her sons. She took in borders at a modest house where she lived, while Brigham and his other wives lived in a grand “lion house” mansion.

After five years, she left her ridiculous marriage and divorced Brigham Young – an unimaginable thing for a Mormon woman to do in 1874.

Her father helped her escape from Utah, after which she wrote a book that became a national sensation. She spent the next decade lecturing about the evils of polygamy. In Women of the West, historian Dorothy Gray writes: “Her impact in rallying public opinion against polygamy was not only effective, but she herself became a successful lecturer.”

Brigham Young and the Mormon hierarchy tried to smear her name by calling her a loose woman, but that didn’t stick, even though to this day, some try to paint her as nothing but a “shrew.”

Unfortunately, her message eventually got trampled in the struggle for the vote. As Gray notes, Easterners mistakenly thought that if women in Utah had the right to vote, they’d repudiate polygamy, so a bill was introduced in Congress demanding the right to vote for women in Utah. (Ironically, this occurred at a time when Congress and most states were vigorously opposing suffrage for anyone else.) Brigham Young knew his people well and knew the women would not rebel. He also knew the women would give his church thousands more votes at the very time that non-Mormons were moving into the territory and challenging Mormon control of Utah. In 1870, the Utah Legislature gave women the right to vote.

“Ignorant of the politics of the state,” Gray writes, “a number of suffrage leaders in the East now looked with friendly eyes on Mormony. As a consequence, the champion against polygamy, Ann Eliza Young, found herself being attacked in the women’s rights press for taking issue with Mormons. To suffragists in the East, the right to vote outweighed even the obnoxious condition of polygamy.”

In 1882, Congress passed the Edmunds Act, which authorized prison time and fines for polygamy. It also declared that polygamists couldn’t vote or serve on juries. The Mormon prophet at the time, John Taylor, went into hiding to avoid arrest, both for being a polygamist and for being the head of the church.

In 1887, Congress went a step further, threatening to confiscate all church property in excess of $50,000 and to dissolve the church as a corporate entity. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the law in 1890. By then, the writing was on the wall. The church’s very existence was threatened by polygamy, and Congress made it clear that Utah would never become a state if it persisted in the practice.

So, the fourth president of the church, Wilford Woodruff, issued a manifesto in 1890 prohibiting polygamy. But not everyone listened. And some insisted that in 1886, former prophet Taylor had had a “revelation” in an all-night meeting with Joseph Smith (who had been dead for four decades by that time) and “The Lord” (whose death is marked by Year One). Taylor is said to have ordained five men to secretly maintain and spread the practice of poly-gamy. In 1933, in an “official statement,” the Mormon Church called this a “pretended revelation,” explaining that there was no record of such a document in the church archives, and also declaring: “No such revelation exists.”

Two years later, the fundamentalists started settling in a remote location on the Arizona Strip, which at the time was called Short Creek. Today, this dark hole of polygamy is known as Colorado City.

When the words “Short Creek” are spoken in Arizona, they are invariably accompanied by the words “destroyed the political career of Governor Howard Pyle.” Twenty years after the community was founded as a home for polygamists, Pyle approved a pre-dawn raid on the town to arrest the men for a variety of sins based on “open and notorious cohabitation.” That was July 26, 1953.

Historian Benjamin Bistline, who was a young man living with polygamist parents during the Short Creek raid, argues another motive: “Colorado City Polygamists.”

“The one charge that was most responsible for the raid was the alleged misappropriation of school funds,” he writes. “And that charge came about because of tax money that ranchers were having to pay to help support the Short Creek School District.”

He notes that the cattle industry paid the bulk of the property taxes in the 1950s to support schools, and the principal of the Short Creek District, Louis Barlow, aggressively went about improving the deplorable buildings and grounds of the school. Although cattlemen probably agreed that the buildings needed repair, they thought Barlow went “too far” when he bought the district a 1946 pickup.

It’s one of history’s delicious ironies that the management of the school district in this very town is again the focus of such rancor. This time, however, the fundamentalists are trying to bleed the district dry and have gone “too far” with the purchase of a jet airplane!

After the raid, 32 men and nine older women were arrested and sent to Kingman. The women and children were told to go home, but when women on the Utah side of the border tried to run, Arizona officials detained all of the women and children and sent them to Phoenix.

It was the treatment of the women and the children that would eventually spoil Pyle’s political career.

The same day the women and children were transported down to the Valley, the polygamists in the Kingman jail were released on bail.

Eventually, 26 of the polygamists would plead guilty to the misdemeanor charge of cohabitation. They got one-year suspended sentences, and went home to Short Creek. It would be another year before their wives and children could go home.

Since then, until only two years ago, politicians in both Arizona and Utah have shied away from Colorado City and the whole issue of polygamy. And in those five decades, the lives and beliefs of the polygamist sect tucked away in Northern Arizona has changed dramatically.

Gone is the rule by the Quorum of 12. Now, all power rests in the hands of the “prophet” – at press time, that was Warren Jeffs.

Gone is the “courting” of men to women who welcome their advances. Now, women are handed out as rewards, and the greatest rewards have been the youngest of the girls.

Gone is education for the children of Colorado City. They’ve been pulled out of public schools and installed in church-run charter schools that teach little more than housekeeping skills. (Nonetheless, Jeffs has kept economic control of the school district and is “bleeding it dry,” the Arizona Legislature has concluded.)

Gone is the value of the young men of the community. They are being driven out because they’re seen as competition for the “child brides” – some girls are as young as 13 when they are forced into marriage with men old enough to be their fathers or grandfathers.

Gone is any semblance of private ownership. All property and all businesses are owned and controlled through a “trust” that is totally controlled by Jeffs. Bistline writes that Jeffs even demanded that people sign over their individual 401-K retirement plans to him.

Warren Jeffs succeeded his father, Rulon, as “prophet” upon the older man’s death in September 2002 – a moment of terror for the community, which was convinced the 90-year-old Rulon would live to be 350 years old.

By the time he died, Rulon had 67 wives, most of them young women. Within seven days of his father’s death, Warren had taken his “mothers” as his own wives – Bistline says that only two women dared stand up to him, and they were exiled.

Then Jeffs went about destroying all other homages to the group’s history. He canceled the annual birthday celebration of a former beloved prophet, LeRoy Johnson. He canceled the annual Pioneer Day to recount the hardships and victories of the early Mormons. He canceled the annual Fall Festival Fair. And he ordered the destruction of a monument that had recently been erected to commemorate the 1953 raid on Short Creek.

But Jeffs inspired such loyalty, that an anonymous threatening letter sent to Bistline to back off on his comments about the community included these words: “We, down to every single last man in Colorado City, will gladly die to protect our prophet. As the mouthpiece of God on this earth we will do whatever the prophet commands us to do to protect the work of God. The best advice I can give you is to stay away from us and let us do God’s will as revealed to us by the prophet Warren Jeffs.”

To many, including officials in Arizona and Utah, Jeffs is no longer leading a “religion,” but a “cult.”

Bistline goes on to warn that no one should take their eyes off of “the prophet,” Warren Jeffs:

“When a dictator believes or purports to believe he is being led by God, and when he also believes that he, too, will become a God, no one can predict the lengths to which he will go or what he will do. It would be a serious error for the government to underestimate Warren Jeffs.”

And so, polygamy’s wild and cult-like legacy continues.