Prison’s tough, but getting out can be even tougher, and that’s where “Women Living Free” comes in. Based at Perryville Prison, it’s an innovative program that gives ex-cons a fighting chance.

Sarah doesn’t look like a three-time loser. In fact, she looks a lot like my fifth grade teacher from years ago. Her short gray hair is so neat, it could be a wig. Her pretty face has just the right amount of makeup. She sits with her hands folded in her lap like ladies used to be taught to do, and she talks softly.

But the orange prison garb she’s wearing gives her away. Still, it’s surprising to find she didn’t land here by accident, but has worn these jumpsuits as her daily wardrobe three separate times in her 48 years. It’s even more jarring when she admits it could be four, if things don’t change.

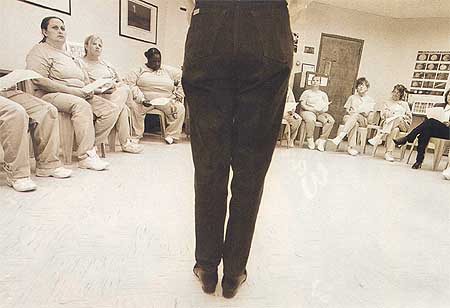

That’s why she’s so grateful to be here, in this classroom at Perryville Prison on a Tuesday night with a group of other orange-clad women, talking about how this time it’s going to be different, because of a new program called “Women Living Free.”

“This program gives me choices,” Sarah says. “I don’t have to feel bad about myself. If I’d been here before, I wouldn’t have gotten hooked up with an abusive male just to pay the rent. This time when I get out I have a nice place to go. I have a job, I’ve worked on my resume, and my kids are seeing this new cycle – they’ve lived through my nightmares, too. Mostly, I’m feeling good about myself. My shame and blame days are gone.”

There are nods and grunts of agreement all over the room, filled with about 20 women. Others here have gone through the revolving door of prison, too. Some are on their first and – they swear – only sentence. They range in age from late-teens to early-60s. Unless they volunteer personal information, I don’t know what they’ve done to be guests of the Arizona Department of Corrections, but they tell me enough to know this: Every woman in this room is a victim of physical abuse, which led them to drugs and thievery and prostitution and extortion and violence.

For Sarah, who eventually tells me she endured 30 years of abuse, it led to prison three different times. And it left her nothing like the strong, determined woman now sitting before me. “I thought I’d just lead my life getting beat up all the time until I was killed,” she says. And too many women in this room know how that feels. One slim, young girl – pretty long hair, beautiful eyes, a gentle smile – slips me a poem she’s written in careful printing called Becoming Free. Later, when I read it, it makes me cry:

At first he was loving, and gentle and kind.

Being so dependent, love made me blind.

At first it was name-calling, but then became more.

“You dumb stupid bitch, you fat, ugly whore.”

I’d cry at his words, because they hurt my heart.

These words were very powerful, they tore me apart.

The poem ends with her vow that nobody like that will ever control her life again, and that she is “healing” and “becoming free.”

But the woman who founded this program and is working a night job to make it a reality, knows that heart-wrenching poems and vows of change are shallow words that make sense behind bars, but too often don’t translate into the free world.

And she’s determined to break the chain that has brought so many Sarahs back behind these barbed-wire-topped walls.

Tracy Bucher is a 40-year-old mother of four from a solid middle class family who founded Women Living Free last year. Already, the Maricopa Association of Governments has named it the number one new program for 2003. Terry Goddard, then the head of HUD and now Arizona’s Attorney General, introduced the program to the community.

Both of those endorsements show how much this program is needed, but it also shows how positive everyone is that Bucher – stylishly dressed in a business suit, talking a mile a minute with her enthusiasm, taking cell phone calls regularly – is the dynamo who can pull it off.

“I’ve watched women go back into prison because they couldn’t find jobs, couldn’t get housing, and had to go back to the abusers who got them in trouble in the first place,” she says over coffee at Park Central.

“The cycle just repeats itself. Over half the women in our program were sexually abused as kids. Fifty-four percent of all children of incarcerated people are in prison themselves. In our class, we have 16 mothers [with] 56 kids. As of last July, seven of those kids were in jail.

“Forty-one percent of the women in our program are in for drug convictions, 25 percent for welfare fraud, 18 percent for violence, and half of that was violence against their abusers. Women are like sponges.”

Once they serve their time and get out, the mountains they face are even higher, she says. “The first time you’re paroled you get a ‘kickout’ of $50. But it costs you $47 for the jeans and shirt you walk out of prison in, so you’re left with $3 in your pocket. When you’re on parole, you have to get a job within two weeks – you’ve been in prison an average of three years, where you’ve been told what to say and when to get up and when to eat – and now you don’t know what to do. Most don’t have any job skills, and nobody has a resume.

“Halfway houses charge you immediately, so you’re immediately in debt. We have a lot of ‘crime-free’ housing in the Valley – they do a background check and if you’ve ever been convicted of a felony, you can’t live there, so that’s one reason there’s such a homeless problem with former inmates.”

Is it any wonder, she asks, that a woman without a safe place to live, without a job, without money, without hope, with one pair of jeans, would go back to the only thing she knows – the man or house or environment that got her into trouble in the first place?

To break that cycle, Women Living Free is a pre-release program for up to 20 women who are 14 to 16 months away from parole. For an entire year, they meet as a group for four hours a week, working on everything from self-esteem to grooming to writing a resume to training for interviews to facing their guilt.

“Women are very guilt-ridden and sorry for what they’ve done,” Bucher says. “They’re so guilty about what they’ve put their kids through. One of the biggest problems is releasing that guilt.”

By the time they’re released, the program has helped them line up a job and given them a free place to stay. A year after they’re out, they must become mentors for new women leaving prison. “We ask for a three-year commitment,” Bucher says. “One in, two out.”

To be in the program, inmates must be enrolled in high school, a GED course, college or vocational classes. If they get in trouble inside the prison, they’re out of the program.

“I’ve been so grateful that so many successful women and men in the community are helping us,” Bucher says. “Our first funders were the Arizona Community Foundation and the Can Do Foundation. We’ve gotten help from the Stardust Foundation and the Nina Pulliam Foundation, and the Symingtons [Fife and Ann] donated money.”

The Salvation Army has donated office space, and Susan Case (of the former Charlie Case Tire Company) bought all the bedding for the duplex halfway house, which Bucher rented with a grant from the governor’s office. The Junior League gave the program all of the leftovers from its rummage sale, and Bucher hopes that will be the start of a money-making thrift shop. But she needs $30,000 to run the program for the next couple of years, and has been raising the money here and there, and with her night-job salary.

Bucher can’t say enough about how wonderful the Corrections Department has been to embrace and advance this program. “Kathryn Brown is the administrator of female programs, and, without her, we wouldn’t have been able to sell this to the central office,” Bucher says. “They’ve been great. They even trusted me enough to issue me a DOC badge – imagine that, going full circle. I was so proud, I wore it everywhere for a week.”

Oh yes, you need to know that Tracy Bucher has firsthand knowledge of the problems of female inmates because she served her own time in Perryville – two-and-a-half years to be exact – for forgery to buy drugs. “I was a first-time offender, a stay-at-home mom who taught Sunday school, but I hooked up with two bad men. I went from a physical abuser to a cocaine dealer.”

While she served her time – her family took care of the four kids – she got training in sales and marketing. When she got out, the first thing she did was get a haircut and a facial. “If I wouldn’t have had my family’s support and a job when I got out.…” She lets the sentence trail off, but you know that option stays in her mind, and is one of the driving forces that has led her to help other women.

“I’ve been clean for 10 years, out for seven,” she says. “I was making great money, but I felt something was missing – I had to give something back. I hooked up with the Arizona Center Against Domestic Violence and developed this program. I bought a book at Barnes & Noble on how to write a business proposal. I got a copy to Terry Goddard when he was the head of HUD, and we were at a meeting one day, and he publicly announced it, to my great surprise. I had to leave, I was in tears.”

With DOC’s help, the first class of Women Living Free convened last July. “At the beginning, these women couldn’t look at you,” Bucher says. “Now you can’t shut them up.” She is obviously pleased to report that change.

I can attest that several head-high, straightforward, gutsy, honest women have embraced this program. At least, that’s who they are now, as I visit them and they spend a good part of their time together telling me their stories.

“This has totally changed our lives,” says Debbie, who’s saving money from her prison telemarketing job for her pending parole. “We all had nothing. Now we have a chance.”

“Women Living Free let me regain myself,” Kelly says. “I didn’t have anything out there – now I do, I have them.”

“Tracy has been here, she covers all the bases and finds people who care,” Julie says. “It uplifts us all to know the world doesn’t hate us.”

“I’m thankful for being in prison, because it was either here or death,” Allison says. “I never really had friends out there – the drug scene – they’re not true friends. Now I have friends.” “We have hope now,” Veronica says.

“So many of us are victims of domestic violence, and that’s not what we deserve,” says Jody. “I have a whole new future – a brand new life. I’m moving to Florida when I get out and taking this program there.”

“My children see the difference,” Sarah says with pride, still looking like my beloved teacher. “My daughter said I don’t even sound like myself. You know, our kids do time with us. My 12-year-old says, ‘Maybe she’s got it right this time.’ They see us taking responsibility, see our strength, and they have it, too.”

Nope, Sarah doesn’t look like a three-time loser, and this time, I’m betting her losing days are over.

To make a contribution, or volunteer time and/or supplies, contact Tracy Bucher at Women Living Free, 602-274-8161 or 623-206-2823.