In the 10 years since his death, Arizona native Cesar Chavez has been honored with a postage stamp and the respect of Senator John McCain. More importantly, his message is now being used to educate children.

esar Chavez is coming home. That’s going to make a lot of people happy, and disgust some others. That’s because Cesar Chavez, who was born in Arizona and died here, wasn’t just a union organizer who fought for farm workers, and he wasn’t just a civil rights leader who preached nonviolence, he was the man who awakened the conscience of a nation and forever changed Arizona politics.

His name still spills off some tongues like a bitter pill, but it rolls off others with awe and pride. And there was a time in this state when it would have been absurd to think of honoring this small, humble rabble-rouser, who was born in Yuma, when everything he stood for was blasted and decried.

But those days are long gone, and although it must gall some, Cesar Chavez is now recognized as a genuine American hero. He was even honored with a national postage stamp last year on the 10th anniversary of his death in San Luis, Arizona. That’s an honor that’s normally not even considered until a decade after a nominee’s death.

Phoenix already has a memorial park in his name at City Hall. And now the state is about to get the first satellite office of the California-based Cesar Chavez Foundation to advance its goal of “educating the heart” of Arizona’s schoolchildren.

All of this takes me back a long way. Within a couple of months of moving to Arizona in 1972, I first saw Cesar Chavez and watched history being made. I attended masses on behalf of farm workers in a little hall in South Phoenix, where I got to know some of his union organizers, and saw in the crowd young Mexican-American men and women who would go on to become Arizona leaders and my friends.

But I didn’t know any of that then. I was just a new kid in town who didn’t even realize that she was watching a powerful civil rights movement take shape.

The second friend I made upon moving to Arizona was Athia Hardt, who is still one of my most cherished friends. I’d come to work at The Arizona Republic, and Athia, a native Arizonan from Globe whose father was an Arizona senator, was already on the staff.

I’d arrived in the state fresh from the University of Michigan, with a bent for stories on social justice. My only concern about moving here, even though I desperately needed a job, was that I saw it as a backward state, where enlightened thought was just about impossible. But I instantly found hope with new friends like Athia. And then there was this amazing movement revolving around Cesar Chavez.

It all began at the statehouse.

The Arizona Farm Bureau had sponsored a bill to outlaw boycotts and strikes during the harvest season – the objective, it seemed, was to make it all but impossible for farm workers to organize a union.

Cesar Chavez – already a potent force in California – came to Arizona in the midst of that debate to argue against the bill. He had hoped to meet with then-

Governor Jack Williams to make his case. (Labor leaders throughout the state were calling the bill “outrageous,” while the growers called it “the most refreshing thing that’s happened in the last 10 years.”)

Just 45 minutes after the bill was passed, Governor Williams had a highway patrolman deliver it to his office so he could sign it immediately. No other bill in Arizona history has ever gotten that kind of special treatment.

The insult was so powerful that a few hours later, Cesar Chavez announced a hunger strike to bring attention to the plight of farm workers – a “fast for love,” he called it, as he retired to a small room in the Santa Rita Center in South Phoenix. The date was May 11, 1972, and it’s no exaggeration to say that that moment would forever change Arizona politics. It proved once again that you can only push people so far before they find the strength to fight back.

Athia Hardt was assigned to cover the daily drama going on in South Phoenix (although, she remembers, “There was a lot of newsroom chatter that this guy was a phony.”) Her newspaper gave prominent play to her articles, which were often sent over the wire to newspapers around the United States.

When she suggested I go along to the nightly masses at the Santa Rita Center, she didn’t have to ask twice. Although I knew little about the plight of farm workers, at that point, I was anxious to learn.

Chavez would appear at the masses – at least until he got too weak from lack of food – and farm worker organizers would report on their campaign to impeach Governor Williams. (Eventually, they’d collect some 168,000 signatures, but the attorney general declared 108,000 invalid, meaning the recall effort failed by 5,000 signatures.)

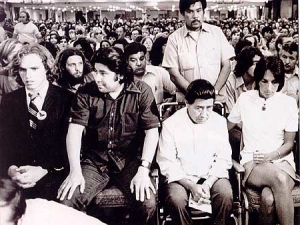

Chavez ultimately fasted for 24 days, bringing attention from around the world and coverage from coast to coast – both The New York Times and Los Angeles Times sent reporters to the little hall in South Phoenix. On June 5, 1972, he ended the fast during a mass attended by some 5,000 people from throughout Arizona and several other states.

But this mass wasn’t held in South Phoenix, it was held in the city’s most popular gathering spot at the time, the Del Webb Townhouse on North Central Ave-nue. Joan Baez sang and then sat next to Chavez, who was so weak that he sat in a wheelchair. Also coming to Phoenix for the occasion was a 19-year-old Joseph Kennedy, the eldest son of Bobby Kennedy – he came on behalf of his late father, to whom the mass was dedicated.

The 45-year-old Chavez ended his hunger fast with communion, and then issued a statement that included these chilling words: “The fast was meant as a call to sacrifice for justice and as a reminder of how much suffering there is among farm workers. In fact, what is a few days without food in comparison to the daily pain of our brothers and sisters who do backbreaking work in the fields under inhuman conditions and without hope of ever breaking their cycle of poverty and misery. What a terrible irony it is that the very people who harvest the food we eat do not have enough food for their own children.”

And those who thought those were just words had a rude awakening at the next election, when an enormous voter registration drive that accompanied the recall attempt sent the first Mexican-Americans and Navajos to the Arizona Legislature. Two years later, Democrat Raul Castro was elected the state’s first Hispanic governor, and Democrats captured the state senate, naming a young activist, Alfredo Gutierrez, as its majority leader.

But Chavez awakened more than just Arizonans. As actor and activist Edward James Olmos has put it, “For Latinos, he was our Ghandi, our Martin Luther King.”

Chavez’s fast also launched the phrase that has come to signify the struggle for equality: Si, Se Puede (yes, it can be done). I heard that phrase several times recently when I went to Phoenix City Hall for the kickoff of Cesar Cha-vez’s return to Arizona.

The Cesar Chavez Foundation wants schoolchildren in Arizona to know that, yes, it can be done – that social conscience and action are a part of citizenship.

This year, they’ve launched pilot programs at Tolleson High School and the Thomas J. Pappas School in Phoenix for homeless children. It’s called “service learning,” and it’s designed to teach youngsters the value of community service.

Among the ideas in Tolleson is to have students collect clothing for the homeless, wash and iron them, and then hand them out. There are also plans to get students involved with construction projects like Habitat for Humanity, and a “gleaning project,” where students would go into harvested fields to glean the leftovers and donate that food to local food banks.

In February, under the sponsorship of the Phoenix firefighters, educators from all 15 Arizona counties came together to learn about the concept of service education and to develop projects for their own communities.

In addition, the foundation is working on a history and archives project, in cooperation with the Smithsonian Institute and UCLA, to collect records and information that document Chavez’s life and his work.

Senator John McCain is even sponsoring legislation in Congress to conduct a comprehensive study of all the physical sites in the life of Chavez, with an eye toward historic preservation. Meanwhile, Hollywood is working on a motion picture on Chavez’s life.

Last month, the foundation sponsored what is to become an annual Phoenix luncheon to raise money for the foundation and remember the contributions of this native son. Many of the “sons” and “daughters” he inspired to join the civil rights movement proudly attended that luncheon.

Maricopa County Supervisor and former Phoenix Councilmember Mary Rose Wilcox was at those nightly masses 32 years ago with her husband, Earl Wilcox, and 2-year-old daughter, Yvonne.

“I’ll never forget the night that Coretta Scott King came to the center,” Wilcox told me. “She picked up my little Yvonne and said, ‘This is what this movement is all about.’ And I thought, yes, it’s about our children. That really launched both me and Earl into political action. I was able to tell Cesar later that I wouldn’t have been in politics without him pushing us to get involved.”

Earl Wilcox would go on to serve in the Arizona Legislature, and for two years, tried to get a bill passed to outlaw short-handled hoes – 2-foot-long tools that require workers to stay bent over all day long. “One time, we had almost 300 people come into the Legislature to testify against it, and at the last minute, the chairman cancelled the meeting,” he says. “We couldn’t even get a hearing!”

Cesar Chavez had personally called Earl Wilcox asking for help on banning the short-handled hoe. So when he was thwarted by the Legislature, Wilcox took a different route, going to the Arizona Industrial Commission and his friend Danny Ortega, who’d also been at those masses at the Santa Rita Center.

The commission studied federal work-place standards and agreed the hoe was wrong. And by a vote of 5-0, they eliminated the short-handled hoe by regulation, to the howls of growers.

“In my 14 years as a lawmaker, that was my proudest moment,” Wilcox says.

And Ortega, now a prominent attorney, says simply that his life of activism “is all about Cesar.”

“My father and mother and brothers and sisters and I all worked the fields,” he says. So Ortega learned early what it’s like to be a farm worker, and he knew right away that he didn’t want to be one for the rest of his life.

“We used to drive out to Tempe on Sundays to see my grandparents,” he says, “and when we drove by ASU, I’d always say, ‘I’m going to go to school there someday.'” He has to stop for a second as he tells the story because his eyes are tearing up and his voice breaks. “My mother would later tell me it hurt her heart to hear me say that because she knew I’d never get there because we had no money. But, of course, she didn’t tell me that. She’d tell me, ‘Of course you can.'”

He beams as he reports that not only did he get a degree from ASU, but so did six of his siblings. And it was during his student days at ASU that Ortega got to know Cesar Chavez and began working for la causa.

He’s involved in the Chavez Foundation today because he’s hoping it will identify and reach a whole new set of committed citizens.

“We’re trying to find young people who have the drive to be risk-takers – who want to do for others, so we can teach them the core values of leadership. If we don’t, we aren’t going to find the world’s next Cesar Chavez.”

And so, Cesar Chavez is coming home. And it makes me proud to be an Arizonan.

For more information on the Cesar Chavez Foundation, call 818-265-0300 or visit ChavezFoundation.org.