Some say his plan is good, some say it’s bad, but everyone agrees that ASU’s ambitious president is taking America’s fifth largest university in a whole new direction. Time will tell if he’s on target.

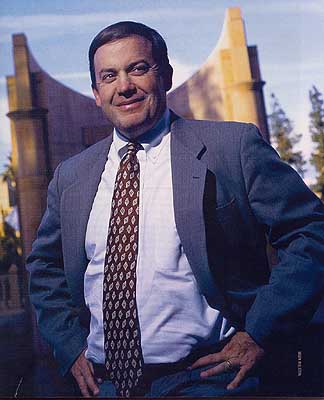

ASU President Michael Crow has been called arrogant, brilliant, arrogant, visionary, arrogant, fearless, arrogant, bold, arrogant…. And with his kind of ego, you could joke that he has the perfect last name. Or, you could say he deserves to crow about his great ideas for ASU, and that the Valley is extremely lucky he came to town.

Legions sing the praises of Michael Crow and his 18-month reign as head of America’s fifth-largest university. Every list of Arizona’s top leaders includes him, and every discussion of the state’s future touts his ideas – sometimes with such glee, you’d think that he invented sliced bread.

When social commentator Richard Florida was in town last fall to tout his book and his ideas about the “creative class,” he told a packed Orpheum Theatre, “The last time I was in Phoenix, I gave this community one challenge – make ASU a world-class university. When they selected Mike as the new president, they blew me away.”

But not everyone who’s been blown away by the new president is happy with the experience. He has a fair number of critics, even if they prefer anonymity and seem terrified that somehow he’ll find out they talked. But they raise important issues, including a concern that his ambitious agenda is intended to boost the stock of Michael Crow, who will then simply wing off to someplace higher on the academic food chain, leaving Arizona to mop up a mess.

They also worry that the changes he preaches are too much, too soon, too risky and far too costly. They say enthusiasm and forward-thinking are nice, but reality has to have some place in the equation. Nobody is saying ASU should remain static – always the second-best university in a state with only three, and ranked an unimpressive 152nd among the best universities in the world. But they question whether the state has the resources or the might to make ASU what Dr. Crow wants it to be: “The leading public metropolitan research university in the United States.”

He’s certainly reaching for a new gold ring. That much we know. But what about him? Who is this new powerhouse that’s so anxious to make such a stretch?

Anyone who thinks Michael Crow should have come to town and taken his sweet old time, learning the lay of the land and the culture of ASU, needs to understand this: He’s known the challenge of being the new kid on the block since he was a little boy.

His dad was Navy and constantly moved the family around the country. He was just 10 when his mother died, and as the oldest of five children, he quickly learned that he had special obligations. He thinks it’s significant that he was the first-born; he knows what psychologists say about that status and agrees that it applies to him. “I’m one of those people driven by being responsible.”

Although he was born in San Diego, he wouldn’t consider it his hometown – his idea of “community” has never been one town, but the whole country. “It was sort of like… well, we’re living in California or Florida or Missouri or Tennessee or Maryland or Virginia or Illinois. So I built this sort of American view – it’s a great country with great places.”

“The favorite childhood memory for me was learning about each place,” he says. “When we lived in California, learning how the ocean worked; in Maryland, learning how to crab.” (Those who have dined with him say he’s retained enormous chunks of that kind of information, and can delight a dinner table with insightful knowledge of obscure pieces of American geography.)

The downside of such a helter-skelter childhood meant he was always the new kid in town, always struggling to find out what was acceptable, what was out of bounds. (Along the way, he even learned that the color of sneakers varied enough from state to state that his color often marked him as a newcomer.) “The challenge was trying to figure out how to adapt without ever caving in your own identity,” he remembers.

At one school, the gym teacher lined up the entire wrestling team and had the new boy wrestle each of them, one at a time. As he remembers it, he was pretty much played out after five guys (two who’d thrown him, three he’d mastered). “I was constantly being tested,” he says.

Not much has changed in his 48 years. He’s still the new guy, and he’s still being tested. And not to draw too fine a bead on it, but you could say they lined up Arizona’s wrestling team when he came to town.

But Michael Crow took on the Arizona Legislature with such finesse that he threw the whole lot and got something everyone thought was impossible. Of course, having not been in town long enough to learn the color of sneakers in these parts, he also got himself thrown out of the governor’s office.

There is no story told with more relish, from both supporters and de-tractors, than the story of Governor Janet Napolitano throwing the ASU president out of her office last year – slamming the door so violently as his derriere crossed the threshold that her DPS guards came running, thinking it was a gunshot.

It all happened in the “heat of battle,” as he likes to call it, when the Legislature was determined to not give ASU $300 million for new research facilities – not in a year when the deficit was about $1 billion and legislators were cutting, not expanding, programs. The governor was determined to get that money for her university system and had been working the legislative halls to force support. How-ever, all on his own, Crow made a few visits of his own, promising to share the largesse expected from the new products and ideas coming out of those new research labs.

When the governor found out he was negotiating behind her back, she called him to the woodshed. And here’s where the story gets really good. Instead of taking his medicine and admitting that it wasn’t smart to be so smart, he asked her if she wanted to react to the facts or to her emotions – he actually said that to the state’s commander in chief. Three seconds later, he was thrown out of her office.

Sitting across from Michael Crow in his conference room on the Tempe campus, the question begs to be asked: “Do you have trouble identifying alpha females?”

He wants to laugh, and does a little (and you’re sure this is the story he’ll take home to his alpha-female wife, Sybil Francis), but this is what he says: “It was no big deal.”

He says the two have since made peace (and a governor confidant confirms that), although no one’s saying if any concessions were made to bring that peace. It’s doubtful, though – since neither is the type to repeat mistakes, neither is likely to be the first to blink.

And certainly he can see, can’t he, that he and the governor are very much alike? “She wants to do a lot and achieve a lot,” he says. “She’s committed to a public purpose and is very focused. She knows what her job is. And I know mine – to build the greatest university we can build.”

And these days in Michael Crow’s mind, all roads lead back to that statement. If single-minded needed a definition, he could be it. Tempe Mayor Neil Giuliano, who has taught at ASU for 21 years, says, “No one gave ASU a snowball’s chance of getting research money. If Michael hadn’t arrived in town, they still wouldn’t have it.”

Giuliano echoes a theme you hear from many quarters in Arizona. “He’s the right guy for the region. If Michael hadn’t arrived in town, the university wouldn’t have changed directions. If Michael hadn’t arrived in town, ASU wouldn’t be building another campus in Downtown Phoenix. All these things are very positive for the region. I’d say that reactions to him are 90 to 95 percent on the positive side.” (Giuliano says that Crow has suggested it’s time for him to move on, and Giuliano’s fine with that. “He’s probably right,” he says, not specifying where he’ll next make a living.)

“I’m a little nervous, but I like that,” says author and creative writing professor Ron Carlson. “You can’t go a week without a big change – that’s unsettling, but that’s not a negative thing. ASU was a very fine school, but a little sleepy. Here comes a guy who’s got huge ambitions, but they’re legitimate – he’s taking this place where it hasn’t been before.”

If the proof is in the pudding, then last year’s private donations are a measure of how sweet Michael Crow is for ASU: The school got more than $115 million in private gifts, the largest amount during any fiscal year over the last two decades.

“You can’t do major change without pissing people off.” It’s a pretty raw statement, but everyone knows it’s true. What’s most remarkable is that Crow hasn’t ticked off more people with his accelerating speed-of-light approach to change at ASU.

But don’t forget that by the time he arrived on campus in July 2002, he’d already had a decade of work for the school under his belt. While he was a provost at Columbia University in New York, he also was a paid consultant to help transition ASU from a school ranked only by its sports teams and its party quotient, to one respected as a research facility. He and his predecessor, Lattie Coor, developed both a working relationship and a friendship.

And the two men couldn’t be more different. Dr. Coor, an Arizona native, is a soft-spoken man who exudes dignity. He did a lot in his 12 years at the helm to take the university forward – he raised tons of money and oversaw an expansion of the university system into both an east and west campus. (“Lattie did a very good job letting Arizona know the importance of the university, getting the bushel off our light,” one insider says.) But he did it with none of the grandiloquence of his successor, who doesn’t need to raise his voice, but isn’t considered soft-spoken and exudes the impression that he’s the smartest guy in the room.

Architect Eddie Jones got it right when he designed the new ASU classroom building named for Coor. “I told myself to remember that it’s about Lattie Coor,” Jones says. “That’s the theme. It’s practical, it’s functional, and it doesn’t pretend to be anything it’s not. The integrity of Lattie Coor is the integrity of this building.”

Crow himself noted the same theme when the five-story tower was dedicated in January: “The building’s grand stature lives up to its namesake. Lattie Coor elevated the university’s status as a major research institution with high-quality academics and a diverse student body.”

Michael Crow, however, isn’t satisfied with elevating the university – he wants to lift it to super stardom. But here’s the rub: While a university is a collection of smart, creative, often forward-thinking people, it’s also known as a culture that views change skeptically, where slow and stodgy are the two main gears. Jokes about the “rarefied air” of a university aren’t far off, either. And there’s often such little connection to the real world from the hallowed halls that a term exists for the distinction between a university and the city in which it exists – town and gown.

Michael Crow’s vision rejects all of that. The question is, what price will the university pay once it’s hitched (or lashed) to his star? Already, plenty of hints are evident, some of which are upsetting many of the folks who rely on ASU for their livelihood or their professional careers.

Consider tenure. In the normal flow of things, professors get advanced degrees and publish papers on their thoughts or research (“publish or perish,” they call it), and if they jump through all the hoops, in the end they’ll earn the golden ring – tenure. Not only is it job security, it’s job protection. You can’t fire a tenured professor for anything less than an egregious infraction. The fact that he or she is a left-thinker or a right-thinker or a controversial voice isn’t grounds for dismissal. Nor is the fact that as president you’ve got a whim that you want to change the direction of the institution, and that particular instructor doesn’t fit with your plan.

So when Michael Crow disrupted ASU’s entire tenure program last spring, it was a cultural shift of seismic proportions. To say the legions who were denied tenure because he thought they didn’t deserve it were upset – people who thought this was nearly perfunctory at this point – is a gross understatement.

“There were some who had not made the grade and some who didn’t make the case,” he explains, as though it’s the most normal thing in the world. “You can’t complain that salaries are lagging and not hold yourself to some standards,” he says, clearly implying that he found the old standards at ASU too lenient.

Those who didn’t make the grade, whose work wasn’t up to snuff, will be looking for jobs elsewhere. Those who didn’t make the case, who didn’t demonstrate clearly enough that they were ready, are being given another chance at tenure, he says.

But that’s not the only thing Crow is doing that’s ruffling feathers.

Consider his insensitivity to the university staff. During his inaugural add-ress, Dr. Crow referred to the staff as “workers,” a stinging appraisal. He now acknowledges that it was the wrong word and says “we’ve taken extraordinary steps” to correct that mistake. “It’s not a word I’ve used since – the staff make the place work.”

And consider salaries. “I got hammered in a three-part series in New Times for executive salaries,” he says, adding that the weekly newspaper had a very selective eye on what he was doing with salaries. “Yes, I increased salaries of executives, but I consolidated those positions into a few people with more responsibilities, but no net increase in cost.

“What wasn’t reported is that I took the 500 lowest-paid people at the university – anybody who was paid below market value – and increased their salaries. I took the top 10 percent of faculty and increased their salaries to whatever level was necessary to keep them from being recruited away. That was last year. This year I gave salary increases to every meritorious employee in the university – other universities in the state didn’t. I’m working on faculty retention.”

Nonetheless, there’s been an abnormally high turnover at ASU. “We have not lost very many people we wanted to keep,” he says without blinking.

And consider women. Yes, Michael Crow acknowledges that the “stars” he’s brought in so far are mainly white males, but he pledges that he’s seeking “outstanding gender and racial diversity” in the university’s leadership, a promise more than a few people are watching with great interest.

And consider tuition increases. On top of last year’s 40 percent tuition hike, expect another 10 percent this year.

“You’re not going to make the university better by making it cheaper,” he says. “You’re going to make it better by enhancing its qualities and its programs and its intensity and its opportunity, all of which costs money. The key is to make certain that students who come from families that don’t have economic means have access to financial aid, and have access to on-campus employment. It turns out that even though tuition in Arizona is 50th in the nation, access to the university is 46th – the state had not built a level of financial aid.”

In other words, Arizona’s low tuition didn’t mean that poor kids were more likely to attend the school. But it did mean that ASU had nowhere near the resources it needed to grow.

But even with the tuition hikes, he’s warned that unless the Legislature approves an extra $58 million for student services, he’ll soon have to cap enrollment, which could keep 5,000 qualified students out of ASU.

Dr. Crow thinks it’s part of the college experience to sacrifice for an education that is so valuable, because it will double your salary over your lifetime. “It’s the largest single return on investment you’ll make in your entire life,” he says. “We’ll keep costs as low as we can, but we need the resources to be competitive.” (Al-though the hikes were hard to swallow, it’s still far less expensive to attend ASU [$3,500 a year] than it is to attend Michigan [$7,800 a year] or Ohio State [$6,600]).

But it’s going to take a lot of financial aid that’s never existed and lots of jobs that don’t exist to make up for the increases that so many middle-income and poor students can’t afford. So, is he concerned about what the university has to give up to reach his lofty goals?

“We have to give up thinking that being good is enough,” he says without flinching. “Being great is much harder. There’s a book called Good to Great, and the opening sentence reads: ‘The enemy of greatness is being good.’ To really be great, to compete at the highest possible levels, requires a kind of total commitment from the university, not a marginal commitment. And that will be hard. Comfort is nice – we all love comfort – but to really step up and compete at the level I think we need to, that really it’s our duty to, you have to give up that comfort.”

Lots of people are very comfortable with a visionary like Michael Crow, and they’re anxious to help.

Businessman and education champion Eddie Basha calls Dr. Crow “one of the smartest men I’ve ever met, and I’m honored to know him.”

Jack Pfister, the retired head of Salt River Project and the “go-to” man for any problem in Arizona, says: “He’s brilliant. He really thinks about as creatively as anyone I’ve ever known.”

But then Pfister adds the caveat that’s often voiced about Crow’s brilliant vision: “The crucial issue is if he has more ideas than ASU has resources to implement.”

Political consultant Jay Thorne, who does work for ASU, has obviously bought into Crow’s vision of progress. “He is not just intellectually brilliant, but he can lay out a vision without a moment’s concern for voters – there’s no pandering, no fear, no baggage, he just makes sense. He’s not constrained by politics.”

That might work in a university where the president is ruler, but it doesn’t sit well in a real world where there’s always a dollars-and-sense checkmate to great moves.

That’s why you also hear, off the record, concerns like this: “When is it risk-taking and when is it irresponsibility?” Or this, “How are you going to pay for all of this?”

If Michael Crow has a fatal blind spot, that might be it. He thinks it’s a foregone conclusion that the growth of the university is a good idea for Arizona, that money for research is demanded, that any roadblocks to the “greatness” of ASU must be broken down. And some say there’s a “shove it down your throat” aura about him.

Perhaps somebody should remind him that he’s living in a state where universities have rarely, if ever, been as high a priority as keeping taxes low.

Tempe Mayor Neil Giuliano acknowledges that Crow “sometimes moves too fast for the folks around him,” but notes that it isn’t a trait unique to Michael Crow. “As an elected official, I’ve been guilty of that myself,” he says.

The one local leader who doesn’t seem to worry about that is Phoenix Mayor Phil Gordon. He has definitely hitched his political wagon to Crow’s horse, and if he’s right, it could be the most important transformation Phoenix has ever seen.

“He just exudes all this confidence – an energy that attracts you to him,” Gordon says of Crow. “He talks about the Valley in terms of its potential – our destiny is still before us. That’s so exciting for me because I really believe it.”

Last December, before Gordon had even been sworn in as mayor, he and Crow announced a partnership to create a Downtown Phoenix campus for ASU – it will be built in the Seventh Street and Van Buren area. And over the next decade, they want to see 12,000 students and faculty there, creating not only a learning center, but an activity center that Downtown Phoenix has always lacked.

As the Arizona Republic rhapsodized in an editorial supporting the idea, all the great American cities have universities – New York, Philadelphia, Chicago (they forgot Los Angeles, but obviously, it does, too). You could almost hear the swoons for the 24-7 activity a university would bring: “A university Downtown would boost construction of new housing and businesses,” the editorial read. “It would give the city a jolt of intellectual energy, creating a welcome environment to professors and students, scientists and entrepreneurs, young people and those who want to harness the energy and idealism they bring.”

Those who think closer to the street saw visions of coffeehouses, jazz bars, more art galleries, black box theaters, a foreign movie house, a place you could have good eggs and bacon and play Scrabble on a Sunday morning.

Dr. Crow knows this Downtown partnership is a hot ticket – he’ll be looking to the city of Phoenix to finance much of this urban campus – and it’s a perfect match for his belief that the university should be “embedded” in the community. “We’re going to grow, and Downtown Phoenix is a place we need to be,” he says.

“We could become the center of knowledge for the state, and that’s an opportunity we can’t let pass,” Gordon says, sounding like a little boy who just got his pony. “I want to make Phoenix the easiest place for Dr. Crow to expand Arizona State University.”

Michael Crow doesn’t cook, but he loves to hike, and he adores his wife and his 4-year-old daughter Alana. He says he wants wife Sybil to think of him as a person “who’s committed to a few things – family and university – and not much else. I’m focused. I’m intense in everything I do – and funny.” He says he wants his daughter to think of him as the funny guy who wrestles with her and reads to her.

The little girl, who’s going to a French-emergence school in Scottsdale, isn’t old enough to form opinions about her father.

But Crow has two older children that he admits already have. His 23-year-old son, Ryan, works in the nation’s capital, helping keep track of Russian nuclear programs. “My son would say I’m intense, focused, serious, unrelenting and funny,” Crow says.

His 17-year-old daughter, Brittany, is a college freshman in New York who is currently going “around and around” with her dad over a rule infraction. Crow says he and his ex-wife both demanded that Brittany’s car could not be loaned out to friends, but it was, and it ended up in an accident. Apparently, Brittany thinks you fix the car and move on – no big deal. Not so. “She thinks it will just go away,” Crow says, and as he says it, you feel an overriding sympathy for the girl.

You want to say to her, “Honey, if you’ve got any of your dad’s smarts, just admit you were wrong, promise you’ll never do it again, and swear this has been a life-altering experience,” because nothing short of that is going to suffice.

Which gives a pretty clear idea of what it must be like to sit around a conference table with the boss, trying to understand his vision.

“We know he’s smart, but he doesn’t have to shove our faces in it,” says a high politico who’s actually in Michael Crow’s corner, but thinks his style is too harsh.

Some say he gives the impression of thinking he’s the smartest guy in the room.

“I don’t view myself as the smartest person in the room, ever,” he protests. “If I come across that way, it’s because my brain, by my own training and background, connects things very quickly, and that may lead some people to see that.

“I view myself as a very good translator between subjects, as a good synthesizer, as a good connector of ideas. I can generate a few ideas and connect a lot of ideas. I work with a lot of people at the university who are smart beyond belief. I also believe there’s different types of smartness or intelligence. I happen to be a person who has a little bit of a bunch of those and I sort of blend them together.”

The other rap is that his approach is “my way or the highway.” And he finds that criticism absurd.

“There is no ‘my way or the highway,'” he says decisively. “That isn’t even a logic that exists in my brain.” But it is the case that if you come to the table unprepared for the process of true collaboration, or if you come only with your own interests, you’re not going to like his style of decision-making. He obviously can’t stand people who easily throw in the towel because the task at hand is difficult.

“You can’t just take off because it’s too hard,” he says. “You have to work at it until we decide together. And some people find that a hard process. Real collaborations are very tough. But there’s no logic that if you don’t do it my way, you’re outta here. That would suggest that somehow I had a plan for everything we’re doing. I don’t. What I have is a strategy. The strategy is that we’re going to move toward more collaboration.”

However, he adds, “I’m not an easy collaborator.”

And he feels the harness of leading such a major institution: “It’s a huge and weighty responsibility. My principal responsibility is to create an environment for success. We’re competing to produce the best ideas, the best students, the best education, to produce the best leading-edge doers and thinkers.”

And he acknowledges two weaknesses. “Sometimes I expect too much from other people. I expect them to get it, or understand it, and everyone doesn’t have the same perspective or experience I do. And because I can run 500 simultaneous equations in my head at one time, that this won’t cause confusion for a lot of other people… I need to think through that.”

Michael Crow has two kinds of perfect days. One gives him the time and energy to work out, be with his family and go to work, all in the same day. The other lets him spend an entire day on a mountain bike and live to tell the story.

If he could have dinner with anyone, living or dead, it would be Winston Churchill or Woodrow Wilson (whose dissertation he studied). He’d like to see the Roman Senate at work. And he’d like to ask Thomas Jefferson, “Why did you allow your children to be slaves?” And he’d love to meet British Prime Minister Tony Blair.

He hasn’t read Bill O’Reilly’s right-wing diatribe or Al Franken’s left-wing diatribe (or Michael Moore’s Dude, Where’s my Country?), but he is reading the new Theodore Roosevelt biography, and he’s read Madeleine Albright’s Madam Secretary. He has The DaVinci Code lying around for when he has a free moment, and he hasn’t yet figured out why the Harry Potter books are so hot. He recently spent good money to take his wife to a Lou Reed concert, and would shell out good money to see Tracy Chapman. Because he has a 4-year-old, he goes to the Phoenix Zoo and the Arizona Science Center a lot. He doesn’t play cards, but likes to play chess against computers.

His last meal would be a Chicago Vienna hot dog (the kind with salad on top). He likes Zinc Bistro at Kierland, Wally’s American Pub ‘N Grill in Phoenix and the Valley’s hottest new gathering place, La Grande Orange at 40th Street and Campbell.

He sees Arizona as “one of those cool places that is still being made, where ideas are still being shaped, and where there’s a creativity a lot of people are excited about.” He finds it a chore when he has to deal with faculty who are only worried about themselves – “That wears me out a little bit.”

And he does admit to being taken aback twice since he came to the university. Once was when a local editorial writer he refuses to name or place asked him in all seriousness, “What’s wrong with being mediocre?” The other was when he discovered that ASU didn’t even have a national media mailing list (implying, of course, that the university never thought it did anything worthy of national attention).

That kind of thinking runs counter to Michael Crow’s vision.

Clearly, he sees the day when everyone in the country knows what a great school, what great research, what breakthrough science, what creative writing, what fine business leaders are coming out of Arizona State University. And he’s poised and ready to march toward that day, promising to stay around until the job is done. (His contract, with its generous annual salary of $468,000, runs through 2005.)

“The soul of this university is fantastic,” he says. “It just needs to grow up.” He might be right, but some would say the same thing about Michael Crow. Time will tell.