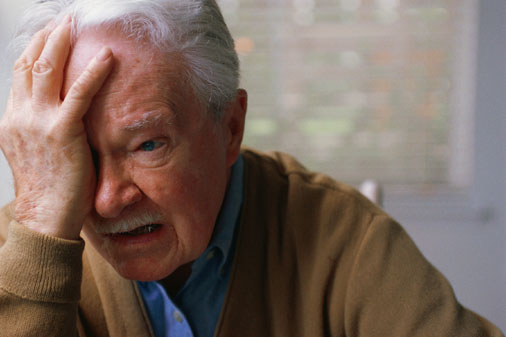

Elder Abuse cases are on the rise in Arizona, thanks to lowly “Body Brokers” who prey on those with little family and lots of cash.

It’s a pretty slimy way to make a buck.

But imagine this as your life’s work: You slip money under the table to nurses in hospitals that cater to the elderly so they’ll identify wealthy patients with little or no family. Then you swoop in just before the patients are to be released from the hospital, knowing they’re confused and scared. A “savior” who could take care of them is just what they need. You present yourself as that savior, promising to get them into a nice, clean, safe home if only they sign a “power of attorney” document.

You whisk them out of the hospital into a “home” that pays you for each new resident. Then you take over their bank accounts and start withdrawing “service fees” and other phony expenses for your new legal duties.

You move them around regularly since you get a new “placement fee” every time they make a change, and as long as their bank accounts hold up, you’re in business.

You take them to a home comprised of less than five unrelated adults, because anyone in Arizona can take up to five paying boarders into their house, provide them with a bed and a communal kitchen – some liken it to having roomies in college – and nobody is going to ask if they’re capable of taking care of these people, if they’ve got enough food in the house, if the place is clean, if they’re being treated with dignity, or if these people even want to be living there. These group homes are considered non-medical boarding houses in Arizona and have no regulations, no oversight.

So unless somebody calls the Phoenix Police Department or Arizona Adult Protective Services and says something is wrong with the situation, nobody will even wonder what happened to that old woman or man next door.

Phoenix Police Detective Toni Brown wants to change that, and she has legions behind her saying it’s time Arizona faces up to its growing problem of elder abuse and exploitation.

“I call them ‘body brokers,’” she tells me, uttering the phrase with true disgust in her voice.

She estimates that only one in 14 cases of physical abuse – and one in 24 cases of financial abuse – of the elderly is ever reported.

“The first reaction is one of embarrassment that they’ve been taken,” Brown says. “So cases aren’t even reported for a long time. I’m backtracking this crime that’s already six months, a year old.”

Of course, strangers aren’t the only ones committing this abuse and exploitation; families can get very greedy and nasty, too. Detective Brown isn’t sure what to do about that, but she is sure about this: Arizona should make it harder for unscrupulous strangers to exploit our elders.

Toni Brown heads the Phoenix Police Department’s Vulnerable Adult Crimes Unit, which was one of the first in the nation when it was created in 2003. She is also the president of the National Association of Bunco Investigators, which is now looking at elder abuse because it’s such a growing problem.

She tells some pretty ugly, stomach-turning stories. Like the one about the “sweet little old lady” who had lived in a licensed group home for years but was nabbed by a “body broker” when she went to a hospital with a broken hip.

“She’s not mentally competent and is schizophrenic, so she does anything anyone tells her,” Brown says

. The woman receives a monthly Social Security check and also had roughly $15,000 in the bank – her nest egg. At the home where she’d lived all those years, the Social Security payment more than covered all of her expenses, so she never had to dip into her savings. But that changed when she was moved to a new home and relinquished her power of attorney to a woman who showed up in her hospital room.

It took less than five months to wipe out her savings. Brown has documented how this woman was exploited and has sent the file to the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office for review. She says she has 17 cases currently awaiting prosecution. Most are accounts of financial abuse; some are of physical abuse.

One of those cases involves an elderly man confined to a wheelchair who was put into one of these unregulated group homes. There were no ramps for the chair, no access for him to get in and out of the house, no way he could go to the physical therapy sessions his doctor had prescribed.

“He was trapped,” Brown says. There was a good reason to keep him trapped – his flush bank account had six figures when he moved in, but it was quickly being depleted. Some $200,000 of it went to pay down the mortgage on the group home.

“They had already taken $650,000 from him when he tricked them into taking him to the bank,” Brown says with admiration. “He told them he had a lot of money in a safety deposit box, but when they got to the bank he said he forgot the key and he’d wait there while they went home to get it. Once they were out the door, he immediately told the banker he needed help, and the police were called.”

Brown says she bets the public doesn’t even know these small group homes aren’t regulated. Still, she’s having no luck in getting new legislation that would close that loophole. The other major problem is that there’s no regulation of companies who send health care workers into private homes to care for the elderly or incapacitated.

“There is no oversight whatsoever in Arizona. We call it the Wild West of home care,” says Don Irish, who helped create the Arizona Non-Medical Home Care Association [aznha.org] a year ago. “You just have to print up cards and you’re in business.” There are no background checks, no skill requirements and no code of ethics, and Irish doesn’t think that’s good enough.

He’s hoping to change that, although his group’s second attempt at getting a bill through the legislature to regulate and license home care workers already appears to have died this year. “The only [governing] body that gives a hoot about [these] consumers is our association,” he complains.

Brown, a 19-year veteran, believes anyone who provides care for a non-relative should be licensed and regulated, as well as trained in care giving, CPR and how to deal with illnesses and death. Getting a license means getting a background check on all employees, as well as being bonded and insured. (She was astonished to find the No. 1 work placement for released convicts was “caregiver.” She’s working with parole officers to stop that, arguing that this is not the profile of someone who deserves the trust to be a caregiver.)

The need for legislation couldn’t be more clear.

“If you’re in a licensed home, every person has a case manager to watch out, inspect and be sure the home is up to code and the person is being cared for,” Brown notes. “If it’s unlicensed, no one is watching, and being lax with care goes hand in hand. This situation is ripe for abuse.”

John Evans coordinates the Arizona Attorney General Office’s role in the Arizona Elder Abuse Coalition. He warns that in the next five years, “we’re headed into the perfect storm” of elder abuse. He thinks the bad economy and the cuts that will affect government and health care – to say nothing of the loss of jobs and depletion of stock-based savings – “will create even more pressure on the most vulnerable people. We’re going to see some devastating circumstances on how these people are exploited.”

Already he says he’s seeing that elderly people living on Social Security are being kept in the family home – even when they need specialized care the family can’t provide – because that check is the only stable income the family has. He thinks things are just going to get worse.

But all hope isn’t lost for those who have either suffered or witnessed elder abuse, because Arizona has lots of resources to help. The Department of Health Services has online lists of licensed homes in Arizona, as well as a deficiency list that notes which homes have been cited for infractions.

Adult Protective Services has a hotline to report elder abuse and exploitation – even if it’s just a neighbor’s suspicion that something is amiss. That number is 877-767-2385 (or 877-SOS-ADULT).

The Area Agency on Aging offers support groups, interim housing and transitional housing through a program called DOVES – the only program in the nation to provide shelter specifically for elder abuse victims. Its 24-hour helpline is 602-264-4357 (or 602-264-HELP).

If nothing else, Brown wants people to start noticing what’s happening to their elderly friends and neighbors. “We want awareness out there so people pay attention,” she says. “It’s incredible the number of elderly people who have no one.”